Bicycle Day: A Myth for the Masses?

Colleagues of Albert Hofmann insisted the Bicycle Day story was made up

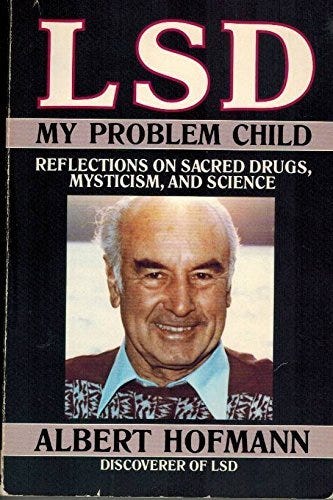

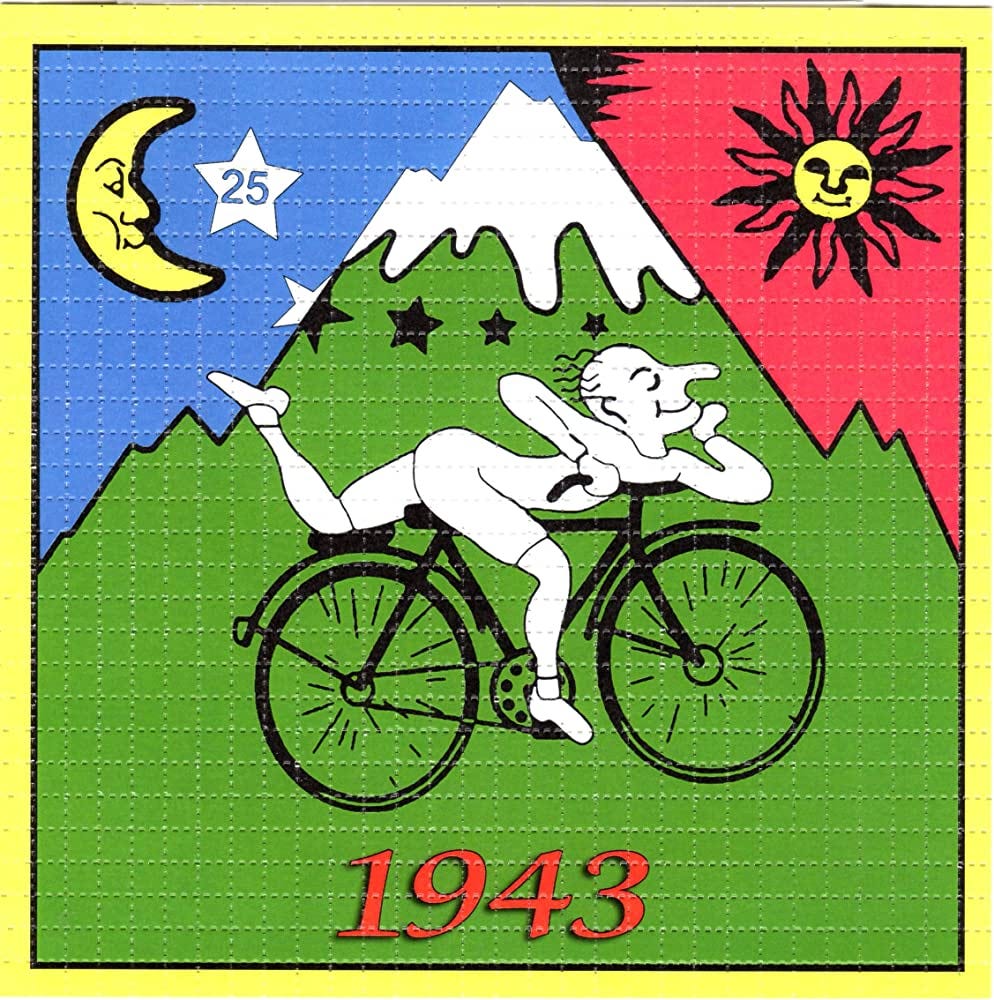

Read any piece you come across online about LSD, thumb through any similar popular magazine article, or pick up any book on the topic—all of them will agree that the world’s first intentional LSD trip took place on April 19, 1943, and involved a bicycle ride in Switzerland. Wikipedia agrees, so it must be true, right?

The mythical event has been enshrined as a holiday among people who use LSD: Bicycle Day, celebrated every April 19th by acidheads the world over. The story behind Bicycle Day is learned and even memorized by psychedelic enthusiasts everywhere. But very few ever question the story’s legitimacy. As we will see, however, it is worth questioning.

The standard narrative

The Bicycle Day narrative, as typically told, is as follows. Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist who worked for the Sandoz pharmaceutical company, was developing drugs to aid circulation, based on compounds found in ergot fungus. He developed LSD as part of this process when World War 2 broke out, at which point he and Sandoz decided to shelve to project.

Years later, Hofmann had some sort of strange feeling, or so the story goes, that he should take another look at LSD. By then, it was 1943, and he decided to pull out the compound again. In the typical Bicycle Day story, Hofmann is said to have accidentally dosed himself when handling the substance on April 16, 1943, and noticed some effects. Intrigued, he then dosed himself intentionally on April 19, 1943. High on acid, Hofmann became too overwhelmed to continue his lab work, and so rode his bicycle home, accompanied by his laboratory assistant, the mysterious “Susi(e) W.”/Susi Ramstein.

According to Hofmann, that day was the first time he fully realized the nature of LSD—that it was an extremely potent compound which could produce profound changes in consciousness. And the rest is history. Or is it?

Colleagues’ contradictory claims

As it turns out, there are a couple of colleagues of Hofmann’s who, in the years since, have claimed that this narrative is not true—or at least, that it is not the whole truth.1 And just what do these colleagues say? You would be right to wonder.

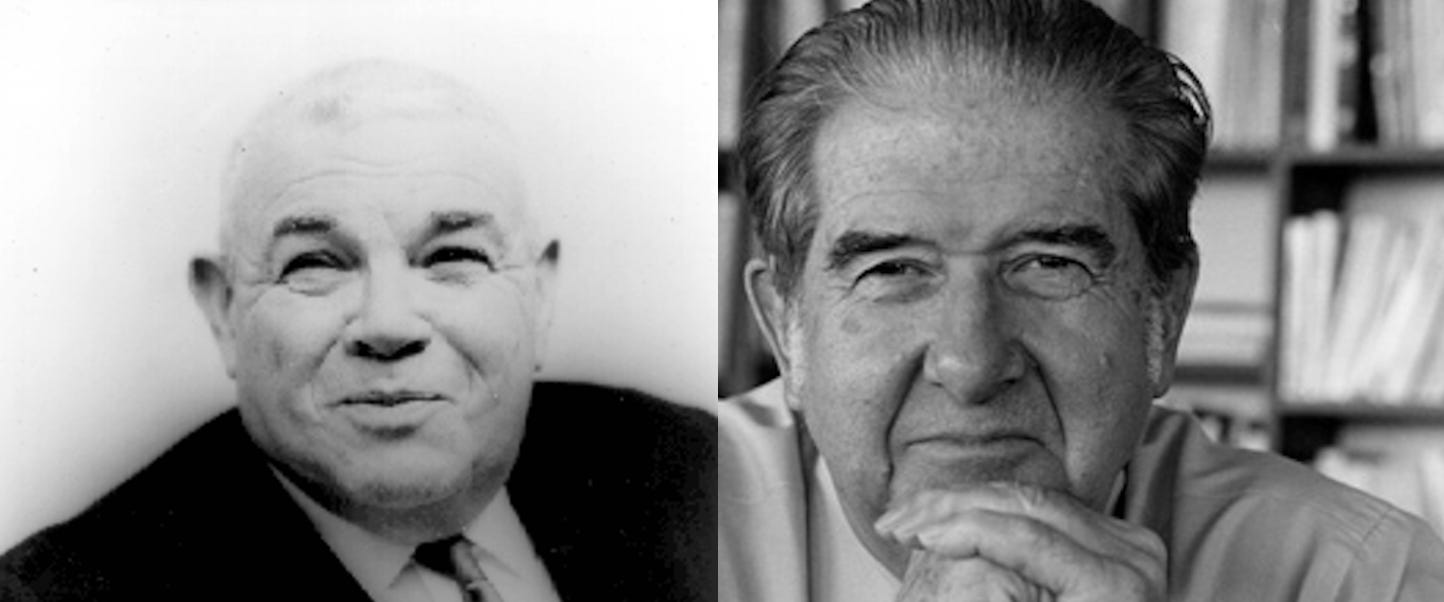

The idea that Bicycle Day is a fabrication comes from none other than “Captain” Al Hubbard and Dr. Willis Harman. Okay, but who are Hubbard and Harman? Their names are not as popular as Hofmann’s, and understandably so.

Al Hubbard and Willis Harman were closely affiliated with the CIA’s MK-ULTRA project in the 1950s and ‘60s. Both Hubbard and Harman worked on various LSD-related projects for the CIA for years. [Not coincidentally, they also both directly facilitated the rise of Timothy Leary; Harman provided Leary with information about LSD, and Hubbard provided him with actual acid.]2

Harman and Hubbard both claim Hofmann knew about the psychoactive effects of LSD since the 1930s and that the Bicycle Day story does not accurately portray the discovery of LSD. This could be entirely irrelevant, or it could be pretty important—exactly which will vary from reader to reader.

What do the sources say?

Most professional news publications ask that journalists confirm their information from at least two separate sources before it is considered true and fit for print as such. But if we are to apply this standard to the Bicycle Day story, it doesn’t hold. Every account of Hofmann’s first (intentional) trip and all claims that April 19, 1943 was the day he confirmed his knowledge of LSD’s psychoactive effects are based on one, single source: Hofmann’s own account.

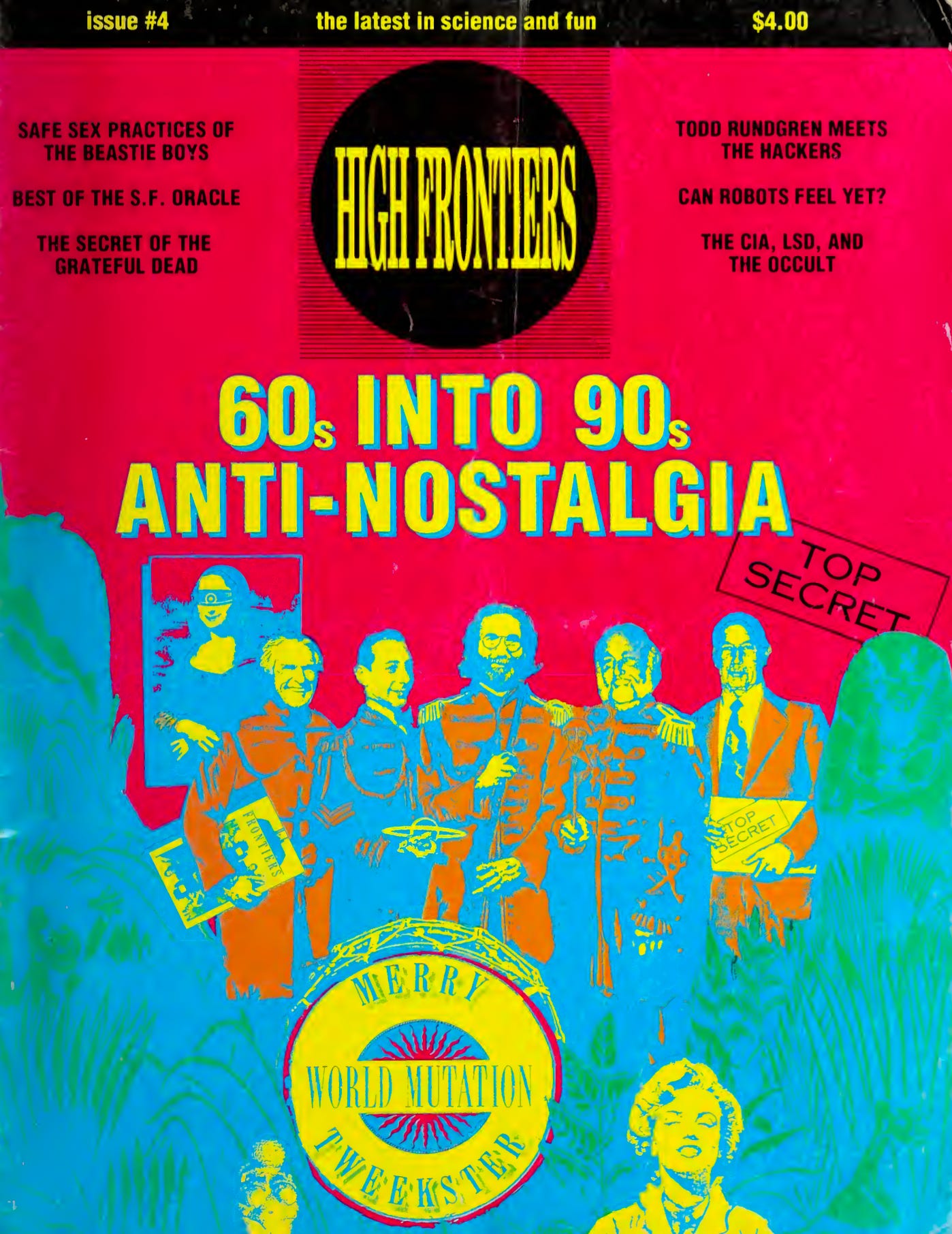

Before we can determine the significance of this, we should take a look at exactly what the conflicting sources say. One of them comes from Martin A. Lee, a reputable LSD historian who has lectured on the topic and published several books. In a 1987 interview with High Frontiers, Lee recalled a conversation he had with Al Hubbard. As Lee explained:

“According to Captain Al Hubbard, Hofmann did not discover it [LSD] in 1943, nor in ’38, but much earlier...According to Hubbard, Hofmann was part of a small group of people who were nominally connected with [Rudolf] Steiner’s anthroposophy group in the early 30’s and they systematically decided to set out to make a peace pill to help mankind. They saw the beginnings of the Nazi emergence, so they consciously set out to make something like LSD, which they did and then kept it secret from the world.” (High Frontiers #4, p. 40-41.)

These details were confirmed and elaborated by Willis Harman in an interview he gave a decade earlier in 1977. When asked how psychedelics became popular, Harman responded:

“The story really starts way back in 1935 with a group of followers of the German mystic Rudolf Steiner who lived in a village in southern Germany. In 1935 a dark cloud was over Europe so the members of this group set out very deliberately to synthesize chemicals which were like the natural vegetable substances which they were well aware had been used in all the world’s major religious traditions down through the centuries. By 1938, they had synthesized psilocybin, LSD and about thirty other drugs. Then they stopped to think about the consequences of letting all of this loose, and decided against it...Five year later, in 1943, when Europe was really in bad shape, they decided apparently that possible negative consequences were nothing compared to the consequences of not doing this.”

“Now,” Harman continued, “two members of this group, which lived in a very tight religious community, were in the Sandoz chemical company—that’s partly how this project came to be. One of them was the chemist Dr. Albert Hofmann. He cooked up the newspaper story, that everyone has heard now, about the accidental ingestion of LSD and the realization of what its properties were after an amazing bicycle ride home and the visions and so on.” (Peter Fry and Malcolm Long, Beyond the Mechanical Mind, 101-102.)

In short, Al Hubbard, who is described by Lee and others as the “Johnny Appleseed of LSD,” emphatically claimed that Albert Hofmann knew of LSD’s effects long before April 19, 1943. And in CIA-collaborator Willis Harman’s own words, the Bicycle Day story, with the “amazing bicycle ride home and the visions and so on,” was “cooked up” by Hofmann to provide a public explanation of LSD’s origin.

In his interview, Harman then goes on to explain how Hubbard and others got involved in LSD research. He does not name the other Sandoz employee who he alleges was part of Hofmann’s group. Based on my research, I surmise it may have been either Werner Stoll or Heribert Konzett, both of whom worked at Sandoz in this period and were affiliated with Hofmann, though I could be wrong.3

What about Susi Ramstein?

There is a single other account of Hofmann’s first trip which lingers in the recesses of the internet. In this piece by Susanne G. Seiler, a woman named “Susi(e) W.” said that she was the “laboratory assistant” who Hofmann wrote “was aware of the self-experiment [with LSD]” and who he asked “to accompany [him] home” on that fateful day.

Another piece writes of a “Susi Ramstein” although it offers no sources or citations other than a single quote from Hofmann’s memoir.

So it seems that Susi(e) W. and Susi Ramstein were one and the same, and that it was in fact she who accompanied Hofmann home from the lab on the day of Hofmann’s first deliberate trip. But Susi’s account does not necessarily conflict with Hubbard and Harman’s claims. Susi has nothing specific to say about the origins of LSD, and Seiler’s piece explains that “Albert Hofmann had already developed LSD-25” when Susi became his lab assistant.

In fact, in Seiler’s entire piece, there are only two, brief direct quotes attributed to Susi herself. The first: “Yes, it's me. I am the Susi you are looking for.” The second: “a good experience,” regarding her own first acid trip in June, 1943. In a three-page piece based on an interview with Susi, those are the only two direct quotes.

Interestingly, at least one component of Susi’s story may conflict with Hofmann’s account of the day. At one point, Susi was afraid that Hofmann might die, and called their colleague, Dr. Arthur Stoll, to tend to Hofmann. Stoll arrived, checked out Hofmann’s condition, and “stayed on to observe him,” wrote Seiler.

But in Hofmann’s memoir, he made no mention of Stoll during the actual trip. Instead, he wrote that “The next day I wrote to Professor Stoll” to tell him about “my extraordinary experience with LSD-25.”

It is entirely possible that Stoll tended to Hofmann during his trip and that Hofmann then wrote to Stoll the next day to tell him more about the experience. Nonetheless, I find it odd that Hofmann’s account makes no mention of Stoll’s presence the day of, and that Susi’s account makes no mention of Hofmann’s subsequent letter to Stoll.

And to top it all off, Seiler’s piece says that the day in question was April 16. This was probably a careless error, but it only heightens my curiosity about the accuracy of the piece.

Onward…

So while Susi’s story may add detail to our understanding of the origins of Bicycle Day, it does not directly contradict the claims made by Hubbard or Harman. If anything, it only further complicates our attempt to clarify what may or may not have happened, considering the differing account re: Stoll and the presumed date typo.

What are we to make of it all? Was Bicycle Day really just a story “cooked up” by Hofmann to satisfy the public? Did Hofmann actually belong to a secret group that wanted to turn on the world and which had been planning this for years before LSD’s supposed discovery?

Based on these facts alone, it is difficult to say for sure what happened. But there is much, much more to this story.

The above information is barely the tip of the massive iceberg that is LSD’s lesser-known history. If you would like to learn more, subscribe to this newsletter. Paid subscribers will receive a physical copy of the book High and Mighty: How People in Power Use Drugs, which covers all of this and more.

Happy “Bicycle Day.”

A prophetic acid novel from the 1930s

Years before the invention of LSD, an Austrian writer named Leo Perutz published an intriguing novel whose basic storyline eerily prophesied the rise of acid and the complicated politics around it. Titled Saint Peter’s Snow and originally published in German in

From Dachau to Baltimore (Part 1)

While Adolf Hitler was getting shot up with oxycodone and administered hits of cocaine on cotton swabs, his underlings were conducting some particularly harrowing drug experiments in the Nazi concentration camps. At the end of World War II, the Allied powers learned of these experiments; they also learned of a new drug called

Piper, Alan. “Leo Perutz and the Mystery of St Peter’s Snow.” Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture, Vol. 6, No. 2, July 2013, p. 175-198.

See also: Rudge, Chris. “Making Madness Before America: Saint Peter’s Snow, ‘psychotomimetics,’ and the German Experimental Imaginary” at https://www.slideshare.net/chrisrudge/making-madness-before-america

This information about Hubbard, Harman, and Leary is obtained from Acid Dreams by Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain

“Nachruf Prof. Heribert Konzett” Medizinische Universität Institut für Pharmakologie, Nov 15, 2004. Online. https://i-med.ac.at/pharmakologie/nachruf_konzett.html