Part 1 discussed the array of drug experiments—many of which involved mescaline—that occurred at Nazi concentration camps in World War II. It then examined how the same people who oversaw and carried out these experiments were recruited to continue their work for the United States after the war.

In Part 2, we’ll see how LSD entered the mix. We’ll also take another look at IG Farben as well as the Quadrapartite Cartel to which it belonged in the 1930s. Finally, we’ll explore how all of this impacted the creation of the psychedelic drug industry that we see today. We will find that several key individuals who have wielded enormous influence in the field have intriguing links to a number of people and businesses affiliated with the CIA—plus a few more Nazis.

“A New Concept of War”

After World War II ended in 1945, the US military’s interest in drugs grew rapidly, thanks in large part to their newfound knowledge of Nazi drug experiments.

The military had already been dabbling in drug research such as the OSS’s attempt to test THC as a truth serum on employees of the Manhattan Project.1 But when they learned that the Nazis had been not just dabbling but fully embracing the most extreme and bizarre drug experiments, the US military-intelligence apparatus saw it as a matter of strategic importance that they find out just what the Nazis were up to in these experiments, and whether it could be replicated.2

Part 1 explained how Kurt Plötner, the Nazi doctor who oversaw the Dachau mescaline experiments, was hired by the US after the war. His line of research was picked up by the US Navy, who carried out similar experiments at a naval facility in Washington, DC. Project Chatter was just one of many research projects instigated by various factions of the US government which focused on the strategic use of drugs.

Project Chatter was launched in 1947. That same year, a chemistry professor from Johns Hopkins University named Alsoph Corwin urged the military to consider the use of drugs which could cause “mass hallucinations and uncontrolled hysteria.”3 This notion took the idea of using drugs for tactical advantages a step further than the original scope of Project Chatter, which was intended to find drugs to aid the interrogation process. Corwin’s use of the term “mass hallucinations” suggested that drugs could be used not only on individuals for interrogation purposes but on entire groups or even populations of people for other strategic reasons.

A couple years later, in 1949, the Army released a special report that laid out the vision for the various developments underway. It was written by L. Wilson Greene and was titled, “Psychochemical Warfare: A New Concept of War.” The report outlined different ways that non-lethal chemical weapons could be deployed for tactical purposes.4 Greene called for the development of a drug that could “incapacitate without killing.”

But only a small handful of people knew at the time that various government agencies were already actively engaged in realizing Greene’s vision. The first director of the Central Intelligence Agency, Roscoe Hillenkoetter, had taken an interest in the idea. He suggested that President Harry Truman assign the task to the new agency, which had just been created in 1947 with the passage of the National Security Act (the same legislation that birthed the Department of Defense in its modern form). Truman took Hillenkoetter’s suggestion.5

Enter LSD

In the interim between Corwin’s call for drugs which could cause “mass hallucinations” in 1947 and the publication of Greene’s report in 1949, something occurred in Switzerland that deeply impacted the course this research would take going forward.

One of the US military personnel who was deeply involved in Operation Paperclip was General Charles Loucks.6 He oversaw many of the scientists hired through the program.7 As a chemical warfare officer for the US Army, Loucks was responsible for monitoring the development of chemical weapons in Europe.8

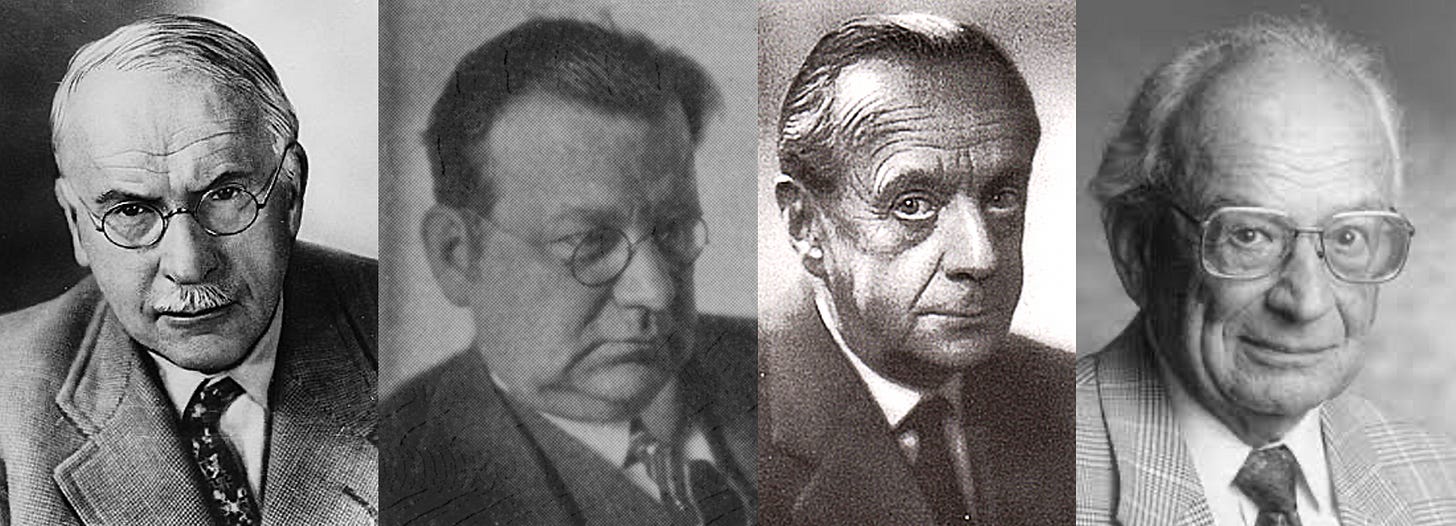

Through this work, he met and became friendly with Richard Kuhn, a Nazi chemical weapons specialist.9 Kuhn ran a medical institute in Germany and was a member of the German Chemical Society. A proud supporter of Hitler, he was nominated for a Nobel prize but rejected it, per Hitler’s request, calling it “a Jewish prize.”10 Perhaps most notably for our purposes, Kuhn worked with IG Farben during the 1930s and served as an advisor to the company.

Kuhn’s expertise proved incredibly useful for Loucks, et al. When Kuhn learned that the US military was looking for drugs which could be utilized for tactical purposes, he told Loucks about a new drug that had recently been developed by a Swiss chemical firm. The drug was LSD. The company, Sandoz.

Kuhn referred Loucks to Werner Stoll to learn more about LSD. Werner Stoll had written the first scholarly article on LSD ever published, in a Swiss medical journal in 1947.11 He was colleagues with Albert Hofmann, the now legendary chemist who invented LSD. Werner’s father Arthur Stoll ran Sandoz’s pharmaceutical division and was himself an expert on ergot alkaloids, a class of compounds he had been studying for decades by that point.

In December 1948, on Kuhn’s recommendation, Loucks took a train to Switzerland to meet Werner Stoll. As Annie Jacobsen explains in her 2014 book Operation Paperclip, this information was not officially documented in any military records. Instead, it was uncovered by Jacobsen in the personal diaries of General Loucks which are archived in Pennsylvania.12

This meeting in Switzerland in 1948 is particularly noteworthy. Why? To the best of my knowledge, this is how the US military first learned about LSD. As far as I know, up til this point they were not aware of LSD. After Loucks’ trek to Switzerland however, LSD quickly became a focal point of the military’s drug research. In this sense, the 1948 Swiss meeting between Loucks and Werner, facilitated by Kuhn, is when LSD entered the picture, so to speak.

IG Farben + the Anthroposophists

Of course, LSD had already existed for 10 years at that point. It was first synthesized by Albert Hofmann in 1938 while he was developing a series of ergot alkaloids for Sandoz. At the time, Sandoz was under the control of the Quadrapartite Cartel, a massive European chemical cartel that dominated the continent’s drug industry for the few years that it existed.

The Quadrapartite Cartel consisted of IG Farben, Sandoz, and a handful of other European pharmaceutical brands and lasted from roughly 1929 to 1939. Due in no small part to its close collaboration with the Nazi regime, IG Farben was undoubtedly the largest, most powerful company in the cartel. LSD historian Martin Lee has suggested that under the cartel’s arrangements, IG Farben probably held the rights to drugs developed by other Quadrapartite companies during the partnership.13

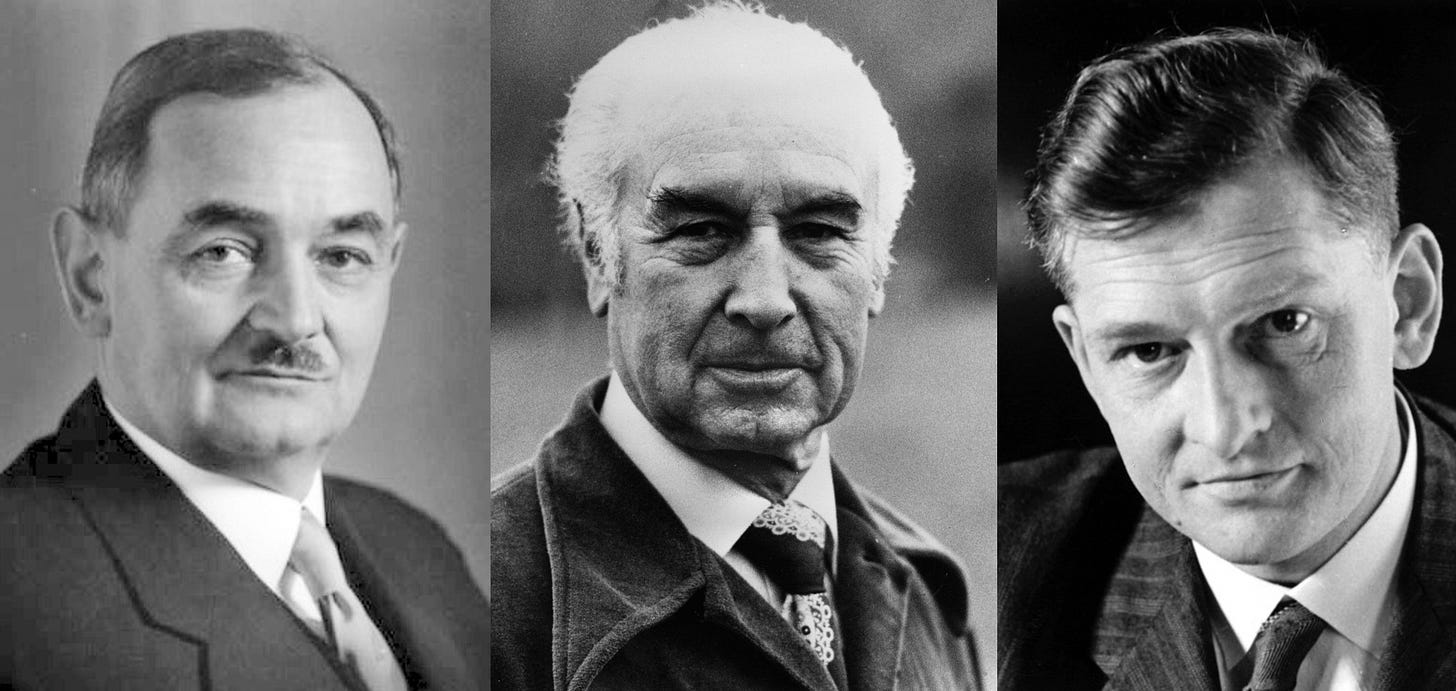

As mentioned in Part 1, IG Farben’s legal business was handled by the Dulles brothers at Sullivan & Cromwell in this same period. Allen Dulles spent time in Switzerland during the war tending to his business with IG Farben while simultaneously working for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). As the war came to an end, he destroyed incriminating evidence, shredding records of IG Farben’s collaboration with the Nazis.14

After the war, Dulles coauthored the National Security Act, which established not only the Department of Defense in its current form but also the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).15 Dulles would assume the role of CIA director a few years later in 1953. His brother John became secretary of state.

The same year that Allen Dulles became the director of the CIA, the agency launched MK-ULTRA. The project continued the themes of the Navy’s Project Chatter but pushed them to new, terrifying heights. Much of the earliest research into LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin in the US was funded—in many cases covertly—by the agency.16

The Quadrapartite Cartel had dissolved by then. But the same Nazi scientists who had overseen much of IG Farben’s work in the previous decade were now working for Dulles’s agency to develop chemical weapons. And, as we just saw, the US military first learned about LSD from Richard Kuhn, a Nazi chemical weapons specialist who himself had worked with IG Farben in the same years in which it was part of the cartel.

It is also worth noting the numerous claims that Albert Hofmann belonged to some sort of secretive group with an interest in the spiritual potential of LSD. Two such claims came to my attention through the work of Alan Piper (thank you, Alan!), who in turn cites interviews with Al Hubbard and Willis Harman. In them, Hubbard and Harman offered similar explanations of LSD’s history. Both claimed that Hofmann was a follower of Rudolf Steiner and belonged to a group of anthroposophists with an interest in psychoactive drugs.

More recently, Robert Forte brought another source to my attention which adds depth to our ability to decipher the potential veracity of these claims. (Thank you, Robert!) It comes from a footnote buried deeply in the back pages of Timothy Leary’s memoir Flashbacks. Therein, Leary described a “group of Swiss and German scholars who took LSD regularly with Albert Hofmann and Ernst Jünger.”17 Leary added for context that Jünger’s writings had influenced Hitler. Jünger notably renounced Nazism in his later years, which Leary attributed to the wonders of LSD, but which seems to me to be a simple careerist decision more than anything else.

Readers may recall from Part 1 that many powerful Nazis were followers of anthroposophy who admired the work of Steiner. Among them, Franz Lippert, who directed the operations at the Nazis’ herbal plantation at Dachau. Lippert used Steiner’s “biodynamic” principles to run the facility, which was fueled by the forced labor of concentration camp prisoners.

The link between the Nazis and anthroposophy was not a casual one. The occultist philosophy concocted by Steiner was politically protected by high-level Nazi officials, many of whom subscribed to it. Meanwhile, other occult groups in Germany were persecuted by the Nazis.

The SS chief and Nazi intelligence officer Otto Ohlendorf later explained that it was “imperative for the overall intellectual development of National Socialism…not to disturb [anthroposophic] research and their institutions, but to leave them in peace, to develop without violent influence from the outside, regardless of the direction of the research.”18

Before we move on, it is also worth noting that Rudolf Steiner and Arthur Stoll shared a mutual connection: Albert Schweitzer. Schweitzer, who was close friends with both Steiner and Stoll, said the following of his friendship with Steiner: “we both felt the same obligation to lead man once again to true inner culture.”

Across the Atlantic

The various social and professional networks that had accumulated around LSD in Europe soon expanded to include a number of US-based scientists who went on to play key roles in the explosive growth of the modern psychedelic industry.

While Allen Dulles was in Europe tending to his business with IG Farben, he met Carl Jung, the famous Swiss psychologist. The acquaintance had been facilitated by Dulles’ assistant (and lover) Mary Bancroft, who was herself one of Jung’s patients. Through Bancroft, Dulles followed Jung’s work closely.19

Dulles was fascinated by Jung’s analysis of Hitler as well as his thoughts on the situation in Germany more broadly. So fascinated, in fact, that he gave Jung a position in the OSS so his various takes could be used for strategic purposes. The legendary psychologist became Agent 488 of the United States Office of Strategic Services.

As David Talbot writes in The Devil’s Chessboard, “Dulles’s reports back to Washington were filled with Jung’s insights into the Nazi leadership and the German people.”20

One of Jung’s followers in this period was Gustav Schmaltz, also a psychotherapist.21 After the war, Schmaltz took up an apprentice named Hanscarl Leuner. Leuner would soon become a key link between the social/professional networks that existed around LSD in Europe and the modern psychedelic boom.

Leuner had served briefly in the Nazi military during the war. Afterwards, he devoted himself to the study of psychology. It was in 1946 that he started training under Schmaltz, the Jungian psychotherapist. After training with Schmaltz, Leuner developed a strong interest in LSD.

In the 1950s Leuner conducted over 1,000 LSD sessions with volunteers and medical patients, which functioned simultaneously as therapy sessions and experiments. Then, in the early ‘60s, Leuner himself took on a student, one who still to this day wields considerable influence in the field of psychedelic studies: William Richards. Richards became interested in psychedelic therapy while studying under Leuner in Germany. We’ll return to Richards in a moment.

I would like to note however, another one of Leuner’s influences: Johannes Heinrich Schultz. Schultz had been on Jung’s radar long before World War II. In his personal correspondence with Sigmund Freud, the two traded thoughts about Schultz’ work. Schultz developed a number of methods which came to be known as autogenic psychoanalysis. The technique combined elements of yoga with hypnosis and suggestibility.

During World War II, the young Leuner studied Schultz’ psychoanalytic methodology. And while Leuner was studying Schultz’ methodology, Schultz himself was busy conducting a number of atrocious medical experiments for the Nazis. Thus, in Schultz and Leuner we see another connection (or two, in this case) between the Nazi regime and the later generation of psychedelic scholars.

The Hoffmann Trip Report + the Amazon Natural Drug Company

Within a few months of its creation in 1947, the CIA had become the primary vehicle for Operation Paperclip.22 The agency set up an office in an old IG Farben building in Germany23 and proceeded to work with a number of Nazi scientists to develop drugs and other chemical weapons.

Compounds were tested at locations like Camp King (a few miles outside of Frankfurt, Germany), as well as Edgewood Arsenal and Camp Detrick (both in Maryland). LSD was just one of many candidates, although it quickly emerged as a favorite. Other drugs tested in these programs include cannabis, cocaine, heroin, amphetamines (including MDMA), PCP, mescaline, DMT-containing epena, Amanita muscaria24 mushrooms, and a substance designated as EA 3167 which produced two weeks of delirium.25

The drugs came from various places. The Army Chemical Corps received drugs that were developed by pharmaceutical companies and rejected due to adverse side effects, some of which were used in military experiments.26 Botanical and fungal substances which were more difficult to obtain were gathered by Fritz Hoffmann, yet another German scientist hired through Operation Paperclip.27

Hoffman worked at a chemical weapons lab in Germany during World War II, making poison gases for the Nazi regime.28 He came to the US in 1947, the same year the CIA was established, and began to synthesize chemical weapons for the US government. When Hoffmann arrived at Edgewood Arsenal that year, he was the first Paperclip scientist to do so.29 Hoffmann befriended L. Wilson Greene (author of the “Psychochemical Warfare” document) and moved in down the street from him.30

In addition to synthesizing deadly gases such as tabun, Hoffmann helped Greene develop the drugs he envisioned for psychological warfare. To achieve this, Hoffmann traveled across the globe to collect various psychoactive specimens, including DMT-containing epena, Amanita muscaria mushrooms, peyote cactus, and more.31

He wrote a report on his research that came to be known as the Hoffmann Trip Report. Published in 1959, it documented the compounds he had studied and developed through his work at Edgewood Arsenal.

Not long thereafter, the CIA oversaw the creation of a new private company to continue searching for drugs in the Amazon. The Amazon Natural Drug Company, as it was called, was directed by J. C. King, a longtime CIA operative.32 King managed a crew of indigenous Amazonian people who were teamed up with professional botanists. They collected samples of plants used to brew ayahuasca, and other botanical drugs, for agency affiliates to study and further develop.

Fritz Hoffmann died under mysterious circumstances in 1966, leading his wife and daughter to speculate whether the CIA killed him out of concern that he would leak sensitive information.33

Baltimore + beyond…

The same year Fritz Hoffmann passed away, another scientist who worked at Edgewood Arsenal, Solomon Snyder, joined the faculty at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.34 He later became the namesake of the school’s neuroscience department.

As many readers will already be well aware, Johns Hopkins is home to one of the largest and longest-running psychedelic research programs in the US. What some people may not know is that decades before their famous psilocybin program took off, Hopkins was the site of a number of CIA-funded drug experiments.35

The Hopkins psilocybin project was conceived in the 1990s by Bob Jesse with input from William Richards and others. To manifest it, Jesse founded a nonprofit called the Council on Spiritual Practices (CSP) while on leave from his position at Oracle,36 a technology firm that was originally launched to serve the CIA. CSP was the conduit through which much of the foundational psilocybin research at Hopkins in the early 2000s was arranged and funded.

Richards already had years of experience administering psychedelic therapy, much of which occurred during his time at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center (MPRC). There, he worked with Charles Savage, the same chemist who had overseen the Navy’s mescaline program (Project Chatter) in the late 1940s. (Also worth noting: John Lilly—who had himself consulted for the CIA—worked at the MPRC in the same period.)

Savage’s mescaline work directly informed MK-ULTRA and the various CIA drug research projects that occurred in the following years. During the MK-ULTRA era, the CIA contracted the pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly to produce nearly half a million dollars worth of LSD for agency’s use. Eli Lilly accepted the task, and they assigned a chemist named Ed Kornfield to oversee the company’s production of LSD for the contract.

Kornfield later became personally acquainted with a younger chemist named David Nichols, who is himself a central figure in the field. Nichols has synthesized not only psilocybin for Johns Hopkins, but also MDMA for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), and DMT for Rick Strassman’s groundbreaking DMT study. He has also synthesized LSD and numerous analogues of it—all for research purposes, of course.37

Speaking of MAPS, they have an interesting connection to Sandoz as well as several links to Novartis, which was formed from a merger of Sandoz and Ciba-Geigy. Sandoz and Geigy both belonged to the Quadrapartite Cartel in the 1930s when LSD was first synthesized. Geigy later merged with Ciba to form Ciba-Geigy, which was in turn merged with Sandoz to form Novartis.

The chairman of the board of directors at the MAPS public benefit corporation is Jeff George. Before joining MAPS, George served as the CEO of Sandoz. MAPS also employs a team of folks who previously worked together at Novartis, which owned Sandoz until a recent spin-off.

These are just some of the plethora of personal and professional connections between today’s psychedelic drug industry and the WWII era of government-backed drug experimentation. We’ll discuss some more in the weeks ahead.

Thanks for reading.

If you found the post interesting, you might also dig these:

What's the deal with neo-Nazis and fentanyl? (Part 1)

Exploring the roots of Nazi and neo-Nazi involvement in the global drug trade

Psychedelic Astroturf for Ukraine

How a neo-Nazi terrorist from Moldova became a "success story" for MDMA + psilocybin lobbyists in Ukraine

Fascinating. I had no idea of the link between Jung and Dulles, and Jung as an agent in the OSS. I want to know more! Thanks for the article.

Biochemist Frank R. Olson, who was murdered by the CIA in 1953, he visited Germany around this time to see operations at Camp King....