I have already explored in great detail how war functions as a stimulus of drug production and distribution. In Drugism, I explained how this process traces back to the ancient history of salt and has since been replicated in nearly every popular drug trend in history. Today we’ll see how commercial trends catalyzed by the Civil War resulted in one of the world’s first documented acid trips, so to speak.

The pitch-like darkness gave way to a phosphorescent light, quickly succeeded by the most beautiful and soft lilac shade of misty brightness, lasting sufficiently long for me to exclaim: “Oh! what a beautiful purplish hue!”

-Dr. Frank Dudley Beane, 1884

The Civil War (1861-1865) had a number of profound effects on the economy of the United States (and the world, for that matter), the consequences of which lingered for generations to come. Among the effects of the war was an explosive growth in the domestic pharmaceutical industry—which, til then, had been meager. The war created a demand for drugs that in turn propelled the proliferation of new pharmaceutical companies during and in the years immediately after the conflict.

The Birth of Parke-Davis

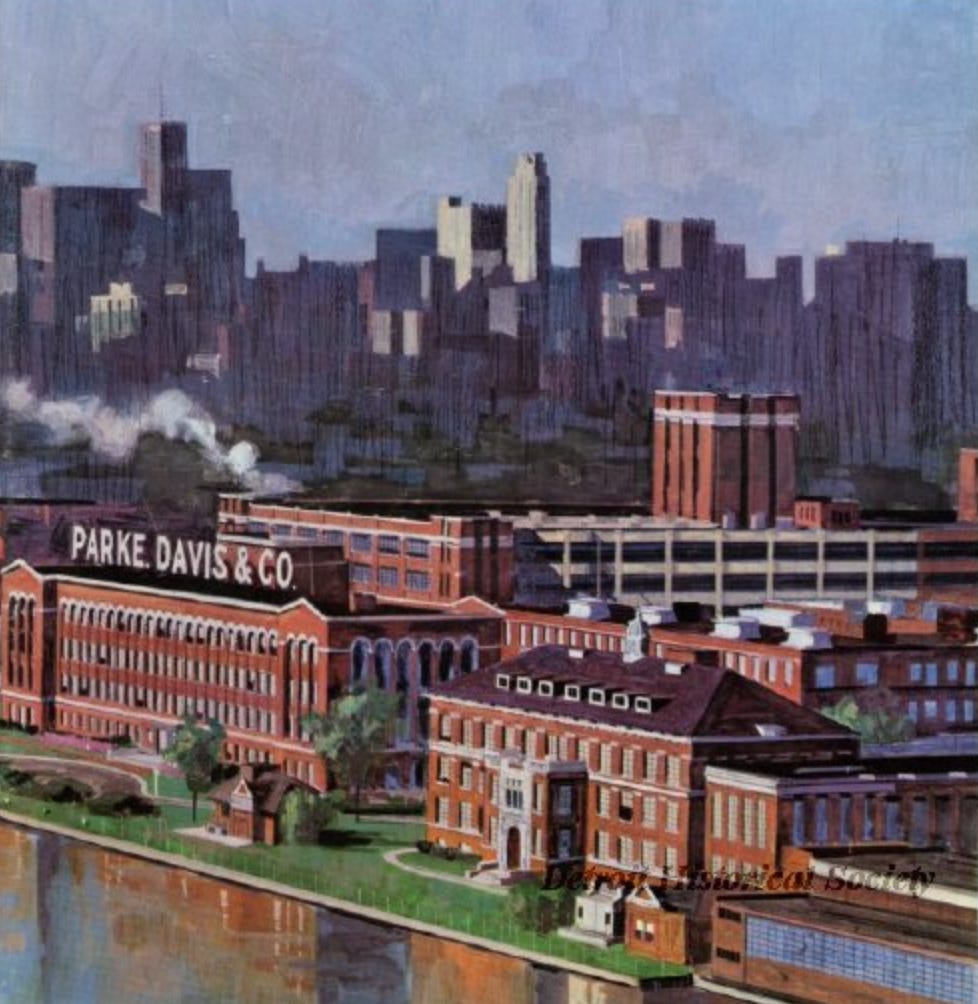

Among the many pharmaceutical companies whose roots trace to this period is Parke-Davis (which has since become a subsidiary of Pfizer). The history of the company began with a small apothecary in Detroit owned by Samuel P. Duffield that sold “elixirs and ointments.” Wanting to expand, he partnered with a businessman named Hervey C. Parke, who was involved with a number of other companies around Michigan and had extensive experience in management.

A write-up from the Detroit Historical Society puts the date of their partnership at 1866, but another source from the National Park Service suggests that Duffield and Parke partnered in 1860. Notice that these two years couch the chronology of the Civil War (1861-1865) quite closely.

In 1867, the firm hired George S. Davis, a “wholesale drug salesman,” to help them further expand their operations. Duffield eventually left the business, leaving the firm to Parke and Davis. The firm became Parke-Davis in 1871, and officially incorporated in 1875.

Less than a decade after Parke-Davis incorporated, George Davis and a physician that worked with the company named Frank Dudley Beane produced a report that represents a seismic event in the protohistory of LSD.

Dr. Beane + Mr. Davis

Beane was an incredibly prolific author of scholarly articles. His work covered a range of medical topics, but focused heavily on drugs. Among them was ergot, which he wrote somewhat extensively about in various medical journals.

During the period in which Beane studied ergot, he partook of a firsthand experience with it that produced a fantastical state of intoxication astoundingly similar to the archetypical LSD trip that became the norm a century later.

During the experience, Beane had Davis, the co-owner of Parke-Davis, on hand to monitor the results, take Beane’s pulse, and help respond should anything go wrong with the experiment. As we’ll see, it was probably a good thing that Beane had a tripsitter that day because the pharmacological menu that he indulged in was truly mind-blowing.

Cannabis + Ergot + Wine + Brandy + Atropine

The trip took place on March 5, 1884. Beane’s experiment began with a liquid extract of cannabis and a liquid extract of ergot, both produced by Parke-Davis. He soon added wine (port) to the mix as well as brandy and atropine. Perhaps needless to say, it proved to be a rather stunning combination that would make even the most courageous Erowid anons quiver.

In his write-up of the experience, Beane claimed that his reason for taking the drugs was that he was suffering from neurasthenia. The term has fallen from use but described a state of “physical and mental exhaustion” and has more recently been likened to chronic fatigue syndrome. Interestingly, this is the same condition that Sigmund Freud claimed to have, that in turn supposedly inspired his cocaine use, which he insisted was a wonderful treatment for it. Freud first got the idea to try coke after reading an industry periodical owned by Parke-Davis.

After consuming the cannabis and ergot tinctures, Beane felt “half-dazed” for a bit.1 He gradually grew more disoriented and was struck with the feeling that his limbs were unbearably heavy—most likely due to the vasoconstriction which is typical of ergot products.

At some point Beane felt “a shock” in which he was “instaneously introduced to the next stage” of the experience.2 Explaining the sensation later, he wrote,

How shall I describe it? To say that like an electric flash an unconsciousness passed over my brain, and that ceberation was instantly awakened…

Beane recalled feeling as if he “was speeding along like the wind,” down a tunnel into “utter darkness.” For a moment, he felt as though he had died. Words, he insisted, only “feebly express” what he felt that day.3

Soon after his sudden-death-flash, he was hit with a vivid stream of hallucinations. As he later wrote,

The pitch-like darkness gave way to a phosphorescent light, quickly succeeded by the most beautiful and soft lilac shade of misty brightness, lasting sufficiently long for me to exclaim: “Oh! what a beautiful purplish hue!”

Beane relished the purple haze. He then fell into “a genuine state of trance.”4 This trance state lasted for some time. Beane also at one point hallucinated that his body was made from wood, describing his various body parts in botanical terms, likening his humanness to other forms of life.

After the more intense hallucinations began to ease up, he entered into a phase of extreme euphoria. He “was contented and happy beyond description, only wishing for indefinite prolongation of this state.”5

He laughed at himself. He exclaimed gibberish in gleeful delight. And yet he was utterly stricken by an inner psychological turmoil amid the shower of giggles and hallucinations. The experience was a roller coaster of intensity, overwhelming him with a barrage of different feelings and perceptions.

He added, “my wife says I cried most piteously for awhile…but I do not recollect [this].”6 He also noted that his “hearing reached the highest pitch of acuteness” and he could “feel [his emphasis] the presence of” others who were nearby but not actually in the room with him.7

In Context

The fact that Beane even wrote this up and published it is a consequence of the Parke-Davis marketing strategy, which heavily relied upon printed periodicals to spread the word about its drugs. This practice placed it in opposition to some other contemporaneous firms, who saw the use of print media for excessive marketing to be fundamentally unethical.

Notice that in the piece, Beane is careful to point out that the cannabis and ergot tinctures he took were produced by Parke-Davis. He even lists the exact names of the products (“Normal Liquid”). But he doesn’t bother to mention what brand of port or brandy he drank. Funny, huh? This report represents commercial drug literature in its purest form.

Eventually, a rival pharmaceutical firm across the Atlantic, Burroughs Wellcome, heard about Parke-Davis’ work with ergot. Stoked by the competition, they hastily set to work themselves to develop a similar class of drugs. Parke-Davis also worked closely with peyote and mescaline in the same period, producing a cascade of events which is itself worthy of close examination for drug historians.

Some decades later, when Sidney Gottlieb was looking for a chemist to assist the CIA with production of new psychedelics, he approached Parke-Davis for help. They introduced Gottlieb to a young company chemist named James Moore (who had worked on the Manhattan Project). Moore became the house chemist for MK-ULTRA. Per Gottlieb’s agreement with the company, Moore’s work with the agency was done under the cover of his position at Parke-Davis. Under this guise, Moore accompanied Gordon Wasson on a trip to Mexico to find and collect psychoactive mushroom specimens for the agency.

To be continued…

A prophetic acid novel from the 1930s

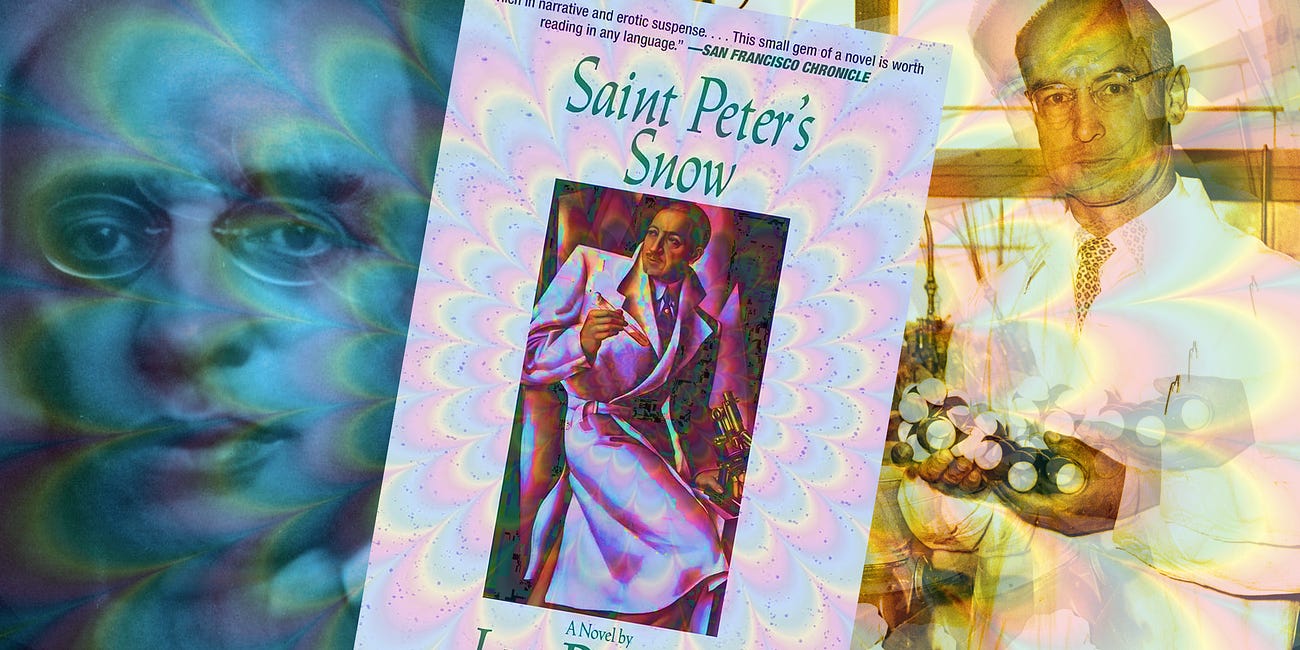

Years before the invention of LSD, an Austrian writer named Leo Perutz published an intriguing novel whose basic storyline eerily prophesied the rise of acid and the complicated politics around it. Titled Saint Peter’s Snow and originally published in German in

See Frank Dudley Beane, “An Experience with Cannabis Indica,” The Buffalo Medical and Surgical Jounral, Vol 23, No 10, p. 446

Ibid., 447

Ibid.

Ibid., 448

Ibid.

Ibid., 449

Ibid.