Petroleum + the Politics of Cannabis Prohibition

Is cannabis a threat to the petrochemical industry? Re-examining Jack Herer's argument about the Marihuana Tax Act, Andrew Mellon, and DuPont

It was a time not unlike our own. The world was on the cusp of war with itself. Every major power was in the midst of several years of economic downturn. Wealth had been drastically consolidated by the elite and the people were hungry. The US government scrambled to absorb some of the shock and ensure that the country survived. Policy in this period was driven in part by a very real fear of a working-class rebellion—pitchforks and all.

There is the old idiom, “drastic times call for drastic measures,” and it would certainly apply to many of the executive actions taken by our government in this period—the Great Depression. The Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 is no exception.

Popular understandings of weed prohibition

There are a number of popular arguments as to why cannabis was so tightly restricted and eventually banned in the US. To many, it was simply a matter of regulating a potentially narcotic substance. Others argue that it was motivated by racism, out of a desire to criminalize melanated communities within the US.

Jack Herer, the famous cannabis activist (and, yes, the namesake of the popular weed strain) believed that the primary motivation for cannabis prohibition in the US was not narcophobia or racism but something else altogether: the financial greed of the petroleum industry. Herer readily acknowledged the narcophobia and racism in cannabis politics, and documented them thoroughly. But he argued that these factors were ultimately byproducts of an even stronger force, money.

Jack Herer’s argument

Herer saw the Marihuana Tax Act as just one part of a larger restructuring of the global economy around petroleum products, a process which began in the late 19th century and has continued to the present day.

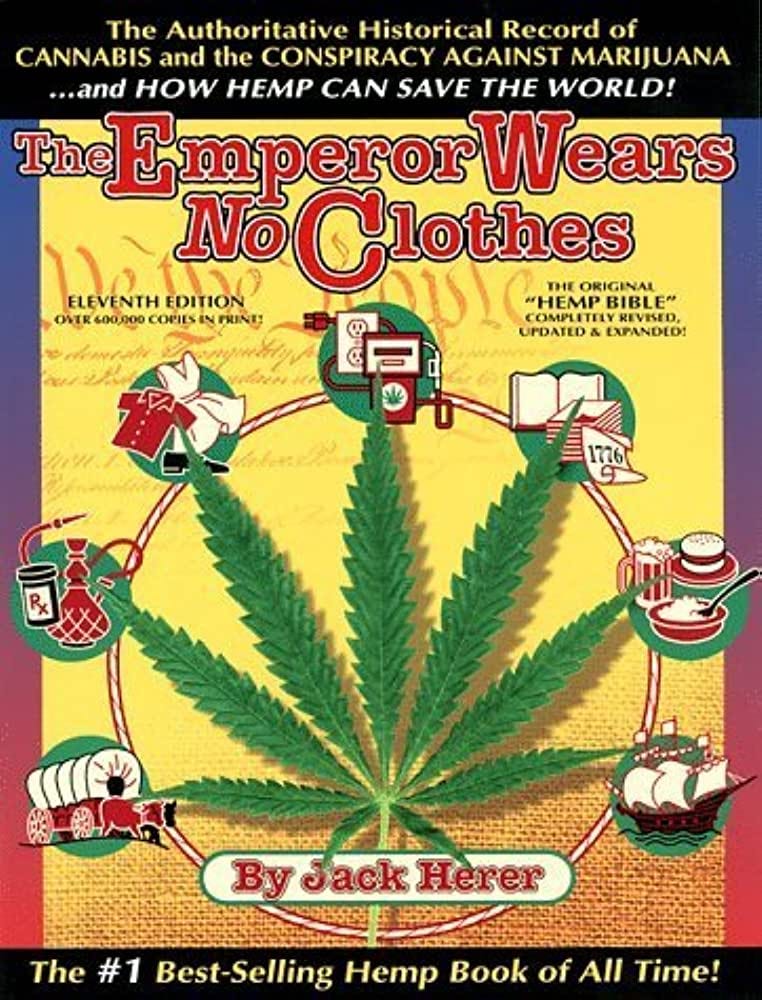

He laid out this argument in detail in his book, The Emperor Wears No Clothes, now a classic (and yet under-read) text among heads and drug history nerds. The book explains not only Herer’s petroleum/prohibition argument but also cannabis history more broadly, and has inspired weed activists for decades. To understand Herer’s argument, we must look—briefly—to the state of the hemp industry before the Marihuana Tax Act was passed.

Historically, hemp was valued for its seed oil, which was commonly used in lighting before the advent of the petroleum industry. Hemp was also a source of fiber, which in turn made paper, clothes, and more. However, although hemp has been cultivated for millennia, it was difficult for US farmers to produce at an industrial scale until roughly the 1930s. This was primarily due to the intensity of labor required for its processing.

Unlike cotton and grains, a machine had not yet been developed which facilitated rapid, mass-quantity hemp production—as, for example, the cotton gin did for cotton or mills have done for grains. But in the early 20th century, technology was developed to process hemp at an industrial scale, in the form of the decorticator. By the 1930s this technology became accessible and affordable to working farmers.1

When hemp processing technology emerged in the 1930s, it meant that working-class farmers could grow and process hemp on their own land. This hemp, in turn, could be used to make not only fuel but dozens of other everyday materials, a market then (and still) dominated by petroleum. And if the agriculture sector could produce adequate fuel supplies, the entire business model of the petroleum and petrochemical industries would be threatened.

Furthermore, the primary sources of hemp at the time were Russia and China. Thus, the invention of the decorticator meant not only that a large, domestic hemp fuel industry might be possible—so, too, would a global market dominated by the US’s primary political competitors.

Herer argued that the du Pont and Mellon families, whose interests lay in the petrochemical industries, were aware of these factors and wanted to stifle the competition before it had a chance to develop.2 This, he explained, was the political context in which the 1937 Marihuana Tax Act was created and passed.

“Social Reorganization”

Herer also argued that the architects of the Act went to great lengths to obscure their motives, so as not to draw protest from the agriculture and pro-labor sectors of the public. The explanation that DuPont gave to their investors at the time is revealing, however.

DuPont's annual stockholder report in 1937 informed investors of impending changes that would benefit DuPont economically. The report anticipated "radical changes" from "the revenue raising power of government" (i.e., the Treasury Department). It wrote of "forcing acceptance of sudden new ideas of industry and social reorganization" for the benefit of DuPont and their stockholders.3 Such "social reorganization" doubtlessly required strategy. The 1937 Marihuana Tax Act, Herer surmised, was part of that strategy.

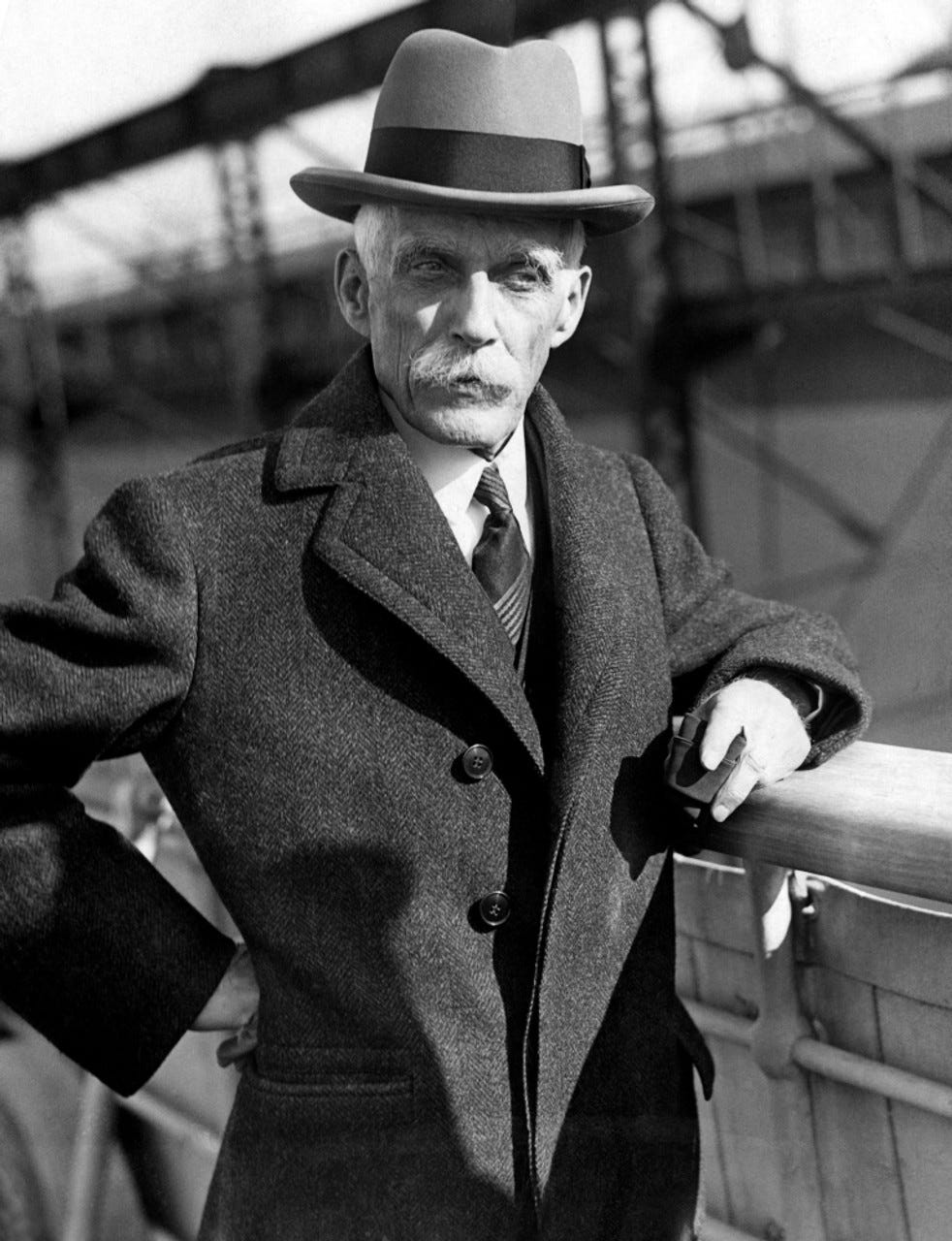

The bill was introduced by Herman Oliphant on April 14, 1937. Oliphant sent the bill to the House Ways and Means Committee, which was chaired by Robert Doughton, an ally of the du Pont family. Needless to say, Doughton approved it. The Act required anyone who legally handled hemp to register with the Secretary of the Treasury, who at the time was Andrew Mellon.4 Mellon was one of the wealthiest men in the US who, just a decade earlier, introduced the Mellon Plan to cut income tax rates of the top income brackets by 50% in order to concentrate wealth in the upper class.5

Harry Anslinger, the infamous poster child and co-architect of US drug prohibition, soon married a niece of Andrew Mellon, but not before being appointed head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. Anslinger assisted DuPont, Mellon, et. al by publicly demonizing hemp as "marijuana," portraying a useful, safe, regenerative source of fuel, medicine, and food instead as a harmful drug that threatened society.

This demonization of cannabis was the public face of the petro-capitalists’ campaign to eliminate hemp as competition, Herer insisted. It would be difficult to convince the general public that they should use expensive foreign gasoline rather than cheap domestic hemp fuel, but they could be taught to fear a drug that supposedly caused insanity, violence, and interracial mingling.

In the years prior to the passage of the act, few people smoked cannabis in the US.6 It was primarily used for its fiber and oil, to make paper, fabric, etc. It was also sold in tinctures for common health issues such as pain or insomnia. Before the politics of petroleum and jingoistic paranoia were attached to it, cannabis was an ordinary substance, rarely seen as any kind of threat. This changed, however, with the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act and its attendant publicity blitz. Cannabis was thus redefined in the public imagination. Its economic potential as a source of food, fuel, and fiber was suppressed for generations.

Most people today think of cannabis as a drug rather than a fuel. What if it what the other way around? If our homes and cars ran on regenerative hemp oil rather than petroleum, and if our clothes were made from hemp fiber rather than nylon, what state would our planet be in? Our health?

Historical context + related policies

Some historical context may allow us to further appreciate the gravity of the sequence of events outlined above.

In the years leading up to the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act, there existed a palpable fear of revolution within the upper echelons of the US government. The severe economic hardship endured by the country’s agricultural sector contributed to a growing distrust of politicians and a desire for change among farmers and the working class more broadly. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his advisors feared a farmer uprising or even a political revolution if they didn’t adequately address the various economic and political issues steeping at the time.7

Simultaneously, a farm of a different sort was emerging, first in Kentucky, then in Texas. These were not just any farm, but Narcotic Farms, so-named because they became the primary institutions in which federal narcotics convicts were sentenced.

Part of FDR’s New Deal was the “New Deal for the Drug Addict,” which ramped up drug restrictions and saw the introduction of federal facilities to “segregate” people who used illegal drugs from the general population. They were be held at the Narcotic Farms, where many inmates were subjected to various drug experiments, some of which were later funded by the CIA. Some of the drugs tested on inmates at the Narcotic Farms were derived from fossil fuels and originated with projects funded by the Rockefellers, themselves a petroleum dynasty.

The first Narcotic Farm opened in 1935, the second in 1939. Chronologically, they couch the passage of the Marihuana Tax Act rather fittingly, while simultaneously exemplifying the tone of the era’s drug policy—increasingly authoritarian and punitive.

The same year that the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, a young man named Richard Nixon graduated from law school. Decades later, after Nixon became the US president, he would further intensify the federal government’s prosecution of cannabis-related charges. Nixon transformed the motley array of drug laws which existed in the US into an authoritarian monolith, known to us as the War on Drugs. The Controlled Substances Act which passed under his watch was a key step in the evolution of this war. And, not unlike the period in which the Marihuana Tax Act was passed, that in which Nixon’s CSA was later passed was also one of economic and political turbulence.

The year after the Marihuana Tax Act passed, another bill was enacted which would impact the future of the drug industry (as well as the petroleum industry and, for that matter, the entire planet). The Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938 increased the authority of the FDA, fostering the relationship between the agency and the emerging domestic pharmaceutical industry. The Act’s passage ultimately led to an increase in use of prescription drugs.8 Many of these drugs themselves were derived from petroleum and other fossil fuels, further enriching the abovementioned petrochemical tycoons.

The simultaneous development of fossil-fuel-derived drugs, the demonization of cannabis, and the growing power of the pharmaceutical industry set the tone for drug use in the US for decades to come. Within a few years, from the establishment of the Narcotic Farms, continuing through the prohibition of hemp via the Marihuana Tax Act, and the passage of the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act shortly thereafter, the entire corporate and political structure of the drug industry in the US was reinvented.

The emerging petro-capitalist elite, such as the Rockefellers and the du Ponts, funded the phenomenon. Their efforts to do away with commercial competition were cloaked in racist, jingoistic messages in order to shock and sway the public. To a large extent, it worked.

In all of this, the immense power of the petroleum industry is clear. That the same industry has had such a directly formative (and negative) impact on drug policy should be no surprise, but it is something rarely discussed.

Thanks for reading.

See Jack Herer, The Emperor Wears No Clothes, throughout Chapter 4, “The Last Days of Legal Cannabis”

Ibid.

Ibid., 55

Ibid., 57-8

One of the more outspoken advocates of the working class in Mellon's era was Fiorello LaGuardia, a New York congressman who later the oversaw the "LaGuardia Report" which protested cannabis prohibition by pointing to the herb’s benign qualities

Drugs and Politics, edited by Paul E. Rock, 57-58

See Eric Rauchway, The Money Makers: How Roosevelt and Keynes Ended the Depression, Defeated Fascism, and Secured a Prosperous Peace, throughout Chapter 5, “A Dollar to Stop Revolution: 1933-1934”

Richard DeGrandpre, The Cult of Pharmacology: How America Became the World’s Most Troubled Drug Culture, 245