I can’t really put it any better than James Bradley, who, in The Imperial Cruise, eloquently explained the vast network of opium money that existed among the US upper class in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He wrote,

“Many of New England’s great families made their fortunes dealing drugs in China. The Cabot family of Boston endowed Harvard with opium money, while Yale’s famous Skull and Bones society was funded by the biggest American opium dealers of them all—the Russell family. The most famous landmark on the Columbia University campus is the Low Memorial Library, which honors Abiel Low, a New York boy who made it big in the Pearl River Delta and bankrolled the first cable across the Atlantic. Princeton University’s first big benefactor, John Green, sold opium in the Pearl River Delta with Warren Delano.

The list goes on and on: Boston’s John Murray Forbes’s opium profits financed the career of transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson and bankrolled the Bell Telephone Company. Thomas Perkins founded America’s first commercial railroad and funded the Boston Athenaeum. These wealthy and powerful drug-dealing families combined to create dynasties.”

Bradley packs a lot of information into those two paragraphs.1 He goes on to explain in further detail how this opium money played into the politics and geopolitics that the US found itself embroiled in around the turn of the century. It is a fascinating story.

I recommend that anyone interested check out Bradley’s work for themselves. But in the interest of public awareness, it seems appropriate to share some of Bradley’s findings as well as some further contextual information. Why? Because the opium trade created wealth that sustained a number of individuals and even entire families—or, as Bradley and others have argued, dynasties—as they came to dominate US political and social affairs for decades to come.

As we will see, the very namesake of Yale University, Elihu Yale, was an official for the British East India Company. When the school was established, it was co-founded by Noadiah Russell, whose family would soon become the largest opium distributors in the US. A number of other families whose names appear across US politics and pop culture, including the Tafts (the family of President William Taft), Delanos (as in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt), Forbses (John Forbes Kerry’s family), Astors (the namesake of the Astoria neighborhood in New York City), and Cabots (benefactors of Harvard University), all made substantial sums of money from the opium trade in China—which, by the way, was 100% illegal at the time, being an utter violation of China’s political and economic sovereignty.

Nonetheless, the stunning amount of money accumulated by US capitalists in the Chinese opium trade and the social network around it would prove absolutely key to not only the drug politics but the politics in general that unfolded in the US and across the world through the twentieth century.

Roots in the British East India Company

Of all the enterprises that participated in the Asian opium trade, the British East India Company was probably the largest. They were certainly not the only company to profit from the Asian opium trade, however. The merchants who sold opium in China hailed not only from Britan but also from China itself, Holland, Spain, the United States, and more.

In the US, many profited from the sale of opium, both to Asian markets and domestically. Interestingly, some of the most successful opium dealers in the US themselves had connections which spanned back to the British East India Company. These connections, in large part, trace to Elihu Yale.

Elihu Yale and the Russell family

Before he became the namesake of Yale University, Elihu Yale was a high-ranking official in the British East India Company. He was in charge of the company’s operations in Madras (now Chennai), which was among a handful of port cities through which opium was shipped eastward. Yale also engaged in human trafficking to supply the labor needs of the British empire. He was eventually fired from the British East India Company after allegations emerged that he’d been pocketing money for himself and cheating both the company and its clients in the process.

When Yale University was later established, its cofounders included among them Noadiah Russell.2 Russell belonged to a powerful Connecticut family that, within a couple generations, grew enormously wealthy from the opium trade.

Russell’s grandson William and William’s cousin Samuel Russell themselves became foundational figures in the US opium business. Samuel Russell, along with Philip Ammidon, co-founded Russell & Company in the early nineteenth century. The firm specialized in opium. They sold it both in China and the US. By the time that Britain waged the Opium Wars on China, Russell & Co. was the largest distributor of the drug in the US.3

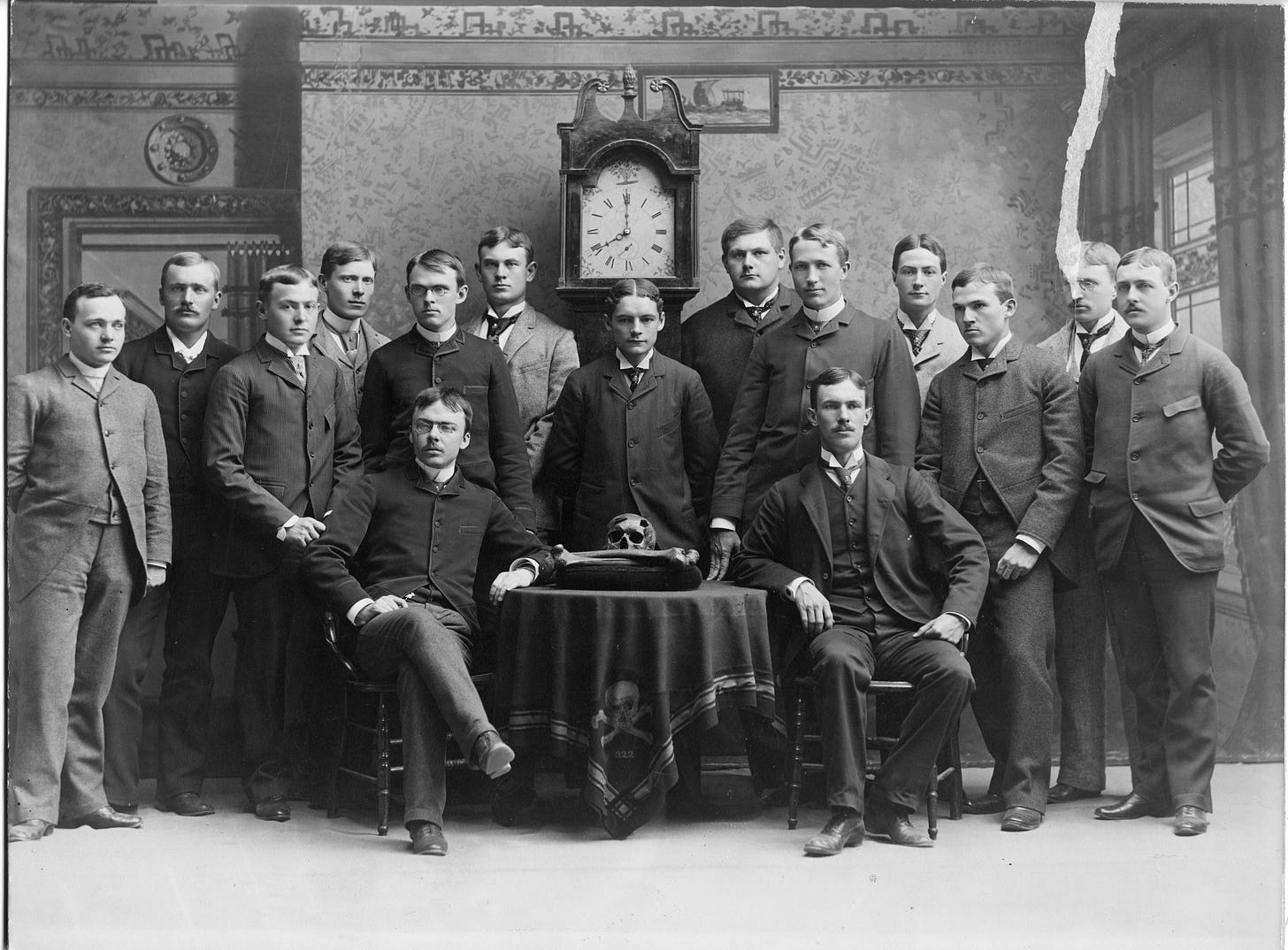

Russell & Company —> Skull and Bones

William Russell, Noadiah’s grandson and Samuel’s cousin, was a Yale graduate and a highly respected general in the US military.4 At Yale, he co-founded Skull and Bones with Alphonso Taft (the secretary of war under President Ulysses Grant and the father of future president William Taft).5 Skull and Bones is, to this day, an exclusive fraternity at Yale that has maintained staggering connections to the federal government, producing three presidents, several secretaries of war (an office that became the secretary of defense after World War 2), and countless other government officials from its ranks.6

Skull and Bones was incorporated as the Russell Trust Association in 1856 by Daniel Gilman, himself a Yale graduate and Skull and Bones member.7 The trust was used to transfer opium profits from Russell & Co. to members of Skull and Bones. At the time, the fraternity’s members were gifted fifteen thousand dollars each upon graduation from Yale, a number equal to nearly half a million in today’s dollars.8

This allowed the company to discretely transfer the profits from its opium business into the hands of their close associates. In the last piece, we learned that the opium trade in China was legally banned in this period, which meant much of Russell & Co.’s business was illegal. By funneling the cash into Skull and Bones, they were essentially laundering the money made from their illegal opium sales in China. According to John Potash, Russell & Co. “unabashedly used the skull-and-bones pirate symbol in its international opium shipping,” thereby signifying the underlying connection between the company and the fraternity.9

Daniel Gilman, UC Berkeley, and Johns Hopkins

After establishing the Russell Trust Association, Gilman held a number of powerful positions. He served as the second president of the University of California, where he oversaw the opening of its Berkeley campus.10 He left the University of California to become the first president of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.11 There, he cofounded the Johns Hopkins medical school and hospital.

Gilman remained at Hopkins as president for twenty-five years. According to a biography of Gilman published by Johns Hopkins, he “was instrumental in the establishment of the university’s educational philosophy, curriculum, and facilities, the hiring of faculty, and the overall administration of the new university.” Clearly, Gilman was an important figure in Johns Hopkins University’s development.

Both UC Berkeley and Johns Hopkins would, decades later, become sites of CIA-funded experimental drug research.12 While this may initially seem irrelevant to Daniel Gilman and Russell & Co., in fact it is not entirely coincidental. There was no shortage of Skull and Bones members among the network that designed the research, which we explore more later. And Gilman’s influence was not confined to managing colleges and opium funds.

After his twenty-five years as the first president at Johns Hopkins University, Gilman then became the first president of the Carnegie Institution. Throughout his illustrious career, Gilman counted among his colleagues and correspondents the industrial magnate Andrew Carnegie, US presidents James Garfield and Theodore Roosevelt, psychologist William James, and many others. He also corresponded with Matthew Arnold and Thomas Huxley, the maternal and paternal grandfathers of Aldous Huxley.13 Aldous Huxley, who was friends with CIA-affiliated doctors and operatives, played a central role in the popularization of mescaline, LSD, etc. in the 1950s and ‘60s.14

Other prominent families with opium money

Gilman was just one of many in a network which grew from Russell & Company. Several others, like Gilman, after doing business with the Russells, acquired enormous wealth and influence. For example, Russell & Co.’s chief of operations was Warren Delano, Jr., the grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Delano sold opium in China for several years, amassing a fortune that propelled him into the New York elite when he returned to the US. He reportedly described the opium business as “fair, honorable and legitimate.” However, his family, and later the Roosevelts who they intermarried, tended not to discuss the source of their wealth, even among each other, according to Geoffrey Ward, a biographer of Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

And they were not the only family to make money with the Russells and later produce a public official.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to High and Mighty to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.