Ukraine, Psychedelic Neo-Colony?

Ukrainian delegation discusses ayahuasca and ibogaine for "psychological optimization" of refugees and veterans

This piece is written in solidarity with the people of Ukraine, who must contend with the violently destructive imperial ambitions of both Russia and the United States.

In yesterday’s post, I said that the next newsletter would further elaborate on the Thaler investigation in Arizona. I am working on that piece now, but I came across something else over the weekend that I feel warrants immediate attention. So, I hope you will forgive me as I detour ever so slightly from my plans to address a topic which I find—and I think you will, too—most urgent.

In today’s edition of The New Yorker, there is a brief piece by Antonia Hitchens titled “Psychedelics for Ukraine.” In it, Hitchens writes that sometime “late last month,” a “Ukrainian delegation” held a gathering at a New York City art studio. But they were not there to discuss art. No—they were there to discuss the possibility of providing drugs like ayahuasca and ibogaine for traumatized Ukrainian refugees and war veterans.

On the surface, this may sound just fine and dandy. Yes, they’ve been traumatized by war, let them have access to the best therapeutic drugs available. I certainly understand this (admittedly quite basic) line of reasoning. But let’s look at it from another angle, shall we?

The delegation included the chaplain for Ukraine’s Territorial Defense Forces, Reverend Serhiy Dmytriyev. With the aid of a translator, Dmytriyev informed the gathering’s attendants of his plans to launch a “special spiritual resilience program” which will, he hopes, “train fifteen hundred military chaplains” for Ukraine.

Another attendant was Jonathan Dickinson, who co-founded Ambio. The New Yorker describes Ambio as “a psychedelic holistic healing company.” A quick trip to their website reveals that the firm employs a combination of ibogaine and 5-MeO-DMT for a variety of medical conditions, including pain, traumatic brain injuries, and neurodegenerative conditions, plus what Ambio calls “psychological optimization.”

At the January meeting in New York, Dickinson explained that Ambio has been working with numerous clients from “US Special Forces” over the past couple of years. Dickinson also shared that Ambio has “a treatment center in Tijuana” where people can access the firm’s ibogaine treatment for $6,500 a pop.

One of the delegation’s attendants was not there physically but joined the conversation by phone, reports Hitchens. His name was Yuriy Blokhin. Blokhin “runs the North American branch of the Ukrainian Psychedelic Research Association.” He shared that he “met an Army Ranger” and the two of them teamed up to provide ayahuasca to “special-ops veterans.”

Blokhin said that drugs like ayahuasca “can become an additional stream of revenue for Ukraine.”

Blokhin spoke excitedly about the potential use of ayahuasca and similar drugs in Ukraine as a treatment for war trauma. Interestingly, he added that “it can become an additional stream of revenue for Ukraine.” In so doing, Blokhin said the quiet part out loud. That this information is couched comfortably in a New Yorker piece amidst cartoons and Netflix ads shows the extent to which selling drugs to fund war-ravaged regions has gained almost complete mainstream acceptance. This time around, the drugs in question have pending FDA approval, something which heroin and cocaine did not when they helped fund the reconstruction of Europe after World War 2.

As Hitchens writes, “Blokhin wants to train therapists who will treat Ukrainian refugees in the use of psychedelics.” He described Ukraine’s government as a “dynamic startup culture” and said that there is now “a critical mass of open-mindedness in Ukraine.” An ideal scenario for “psychological optimization,” no?

Such ideas fell on receptive ears in the New York City art studio that day. There were others there who, like Blokhin, seek to promote the use of tryptamines and phenethylamines to treat the symptoms of war-induced PTSD.1 It’s an idea that, despite its dystopian undertone and questionable supporting evidence, has fascinated not only the war machine but also the corporate press and, increasingly, the well-meaning public in recent years.

One attendant who seemed to be totally on board with such ideas was Leah Drew, who The New Yorker describes as a “mind-set mentor.” Drew’s website advertises her as a “rehab specialist” and “online coach” who helps clients “control” and “optimize” their health. It beckons the viewer to join “The Holistic Healing Tribe” for “optimized self-healing.”

“We have this idea that war is super depressing, super ugly,” Drew said at the gathering. “But it can be empowering.” Wait—excuse me? No shit, war can be empowering—that’s exactly why the world’s rich funnel tens of billions of dollars into it year after year. But then again, most of the people in the room that day were probably well aware that war can be empowering. They may have also agreed with Drew when she stated that “there’s positivity in trauma.” But go tell that to the refugees.

Drew says “there’s positivity in trauma.” Go tell that to the refugees and those who have lost loved ones in the war.

Drew’s attempt to recast trauma as “positive” and war as an “empowering” mental health challenge is frankly disgusting. Yet it represents an increasingly popular strain of thought within the current cultural debate on the role of drugs in and around warfare. And it is an attitude which pairs wonderfully with the military industrial complex’s fascination with MDMA, psilocybin, DMT, ayahuasca, ibogaine, etc.

Almost as if to ensure that these ideas came across as hip, the delegation’s meeting was hosted, as mentioned above, in an art studio in New York City. The studio is where Agniekszka Pilat does her work. Pilat is an artist whose work depicts robots with imagery meant to evoke the feeling of “religious icons” and “royal portrayals of noble ancestry.” Her website says that her work is intended to be viewed by “both humans and machines.”

The robots that Pilat uses for inspiration are loaned to her by Boston Dynamics. Boston Dynamics is a robotics company that was launched largely with funds provided by the US military and which makes robots for DARPA. Pilat has also done an artistic residency on a US Navy vessel, the USS Hornet, which she depicted in an abstract, multi-hued four-by-four foot oil painting.

At the psychedelic-Ukraine-themed gathering, Pilat spoke about the world’s “fatigue with the war,” lamenting that the public was losing interest in the Ukraine conflict. But such discussions of trendy drugs like ayahuasca “might make it a ‘sexy’ conversation again,” she said.

Such discussions of trendy drugs like ayahuasca “might make [the war in Ukraine] a ‘sexy’ conversation again,” said Pilat.

Welcome to 2023, where trauma is positive and war is sexy (or at least wishes it was).

To those who are thoroughly indoctrinated in psychedelic ideology, this may all come across as lovely. And rest assured that I am quite familiar with the various arguments in favor of providing such drugs to military personnel, veterans, and refugees. I understand their logic, and to a degree I even agree with some of them. To take it a step further, I believe that everyone should have access to a safe and regulated supply of the drugs of their choice, regardless of their reason for using.

But I ask that we not lose hold of our critical thinking skills when examining such phenomena. Yes, drugs can be great for healing. Absolutely. And yes, ayahuasca, ibogaine, etc. are very powerful organically-derived substances with centuries or possibly even millennia of indigenous use. I understand all that, and spent many years proselytizing about it.

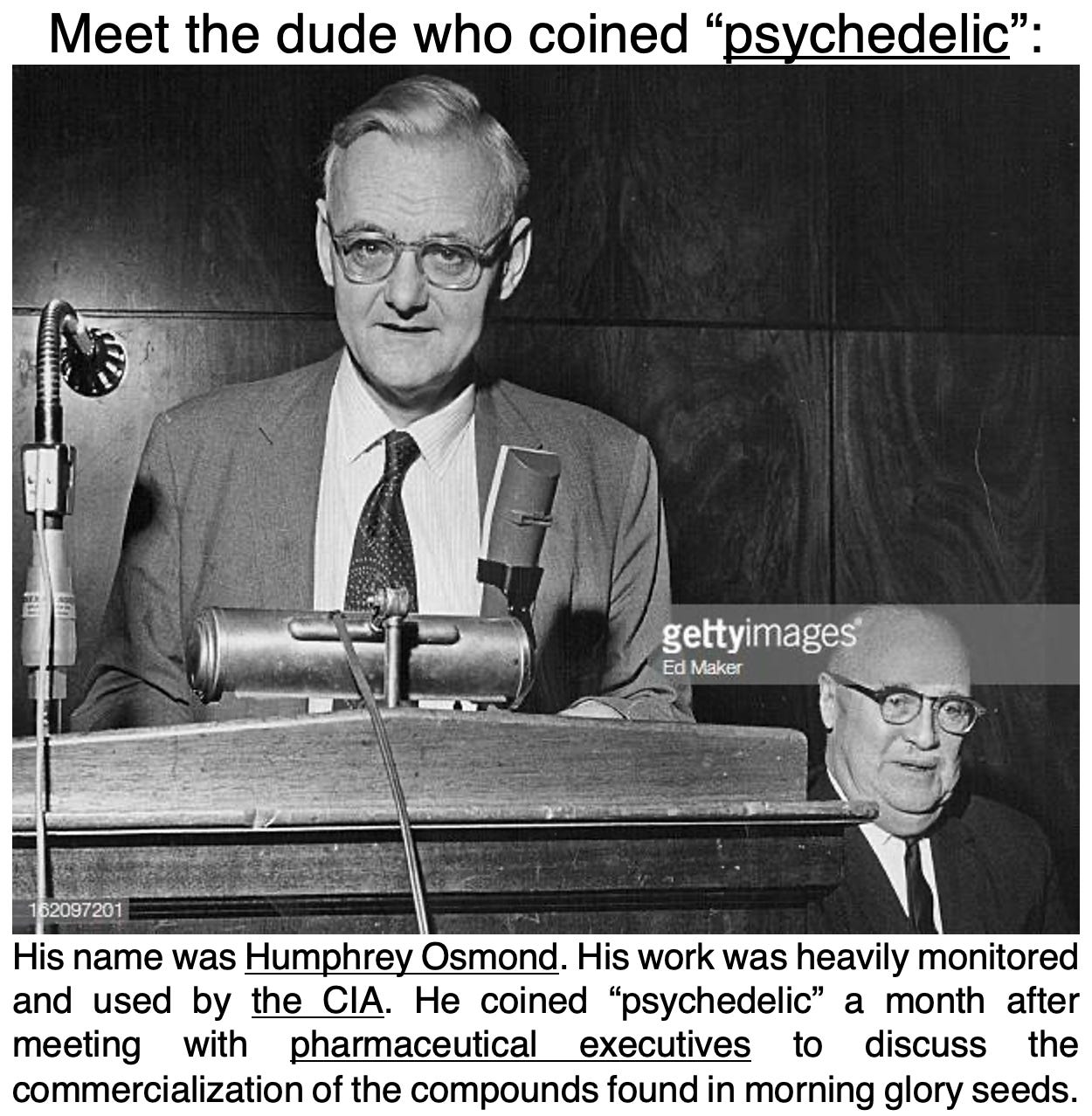

But these drugs—ayahuasca, ibogaine, and just about every other substance that is typically considered “psychedelic”2—all have histories of use in various state-sponsored mind control experiments which have been thoroughly documented via multiple FOIA requests, declassified documents, and firsthand interviews. In fact it was through such research that the corporate medical establishment learned about these substances and developed the idea to use them as mental therapeutics. And if their actions are any sign of their intent, the slew of companies currently engaged in the corporatization of these drugs are motivated as much by the money as they are by altruism.

Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky met with top CIA officials in January, just a few days before the psychedelic Ukrainian delegation gathered in New York.

So I ask: might there be ulterior motives in this effort to provide Ukrainian war refugees and veterans with so-called “psychedelics”? What do you think about all of this? Can you, too, see how there might be various reasons to remain critical of such efforts to employ ancient indigenous medicines in what is essentially imperialist apologetics in pharmacological form? Is anyone else troubled by the cultural monopoly which the military industrial complex maintains around these drugs? Let me know in a comment!

For some more background on drug-related activities in Ukraine, check out my piece Drug Trafficking in Ukraine. In it, I discuss the history of drug trafficking in Ukraine since the fall of the Soviet Union; the piece also mentions that Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky met with top CIA officials in January, just a few days before the above-described delegation occurred in New York. Considering the CIA’s long history of involvement with “psychedelic” drugs, this seems to be something worth noting.

Given the highly dynamic and rapidly evolving nature of the subject at hand, I will revisit these topics (Ukraine, drug trafficking, corporadelia, etc.) as new factors are introduced and conditions change.

Thanks for reading.

Advocates argue that these drugs treat the “root cause” of trauma, but gobbling MDMA doesn’t stop wars—even if a million blissed out ravers insist otherwise.