What's the deal with neo-Nazis and fentanyl? (Part 1)

Exploring the roots of Nazi and neo-Nazi involvement in the global drug trade

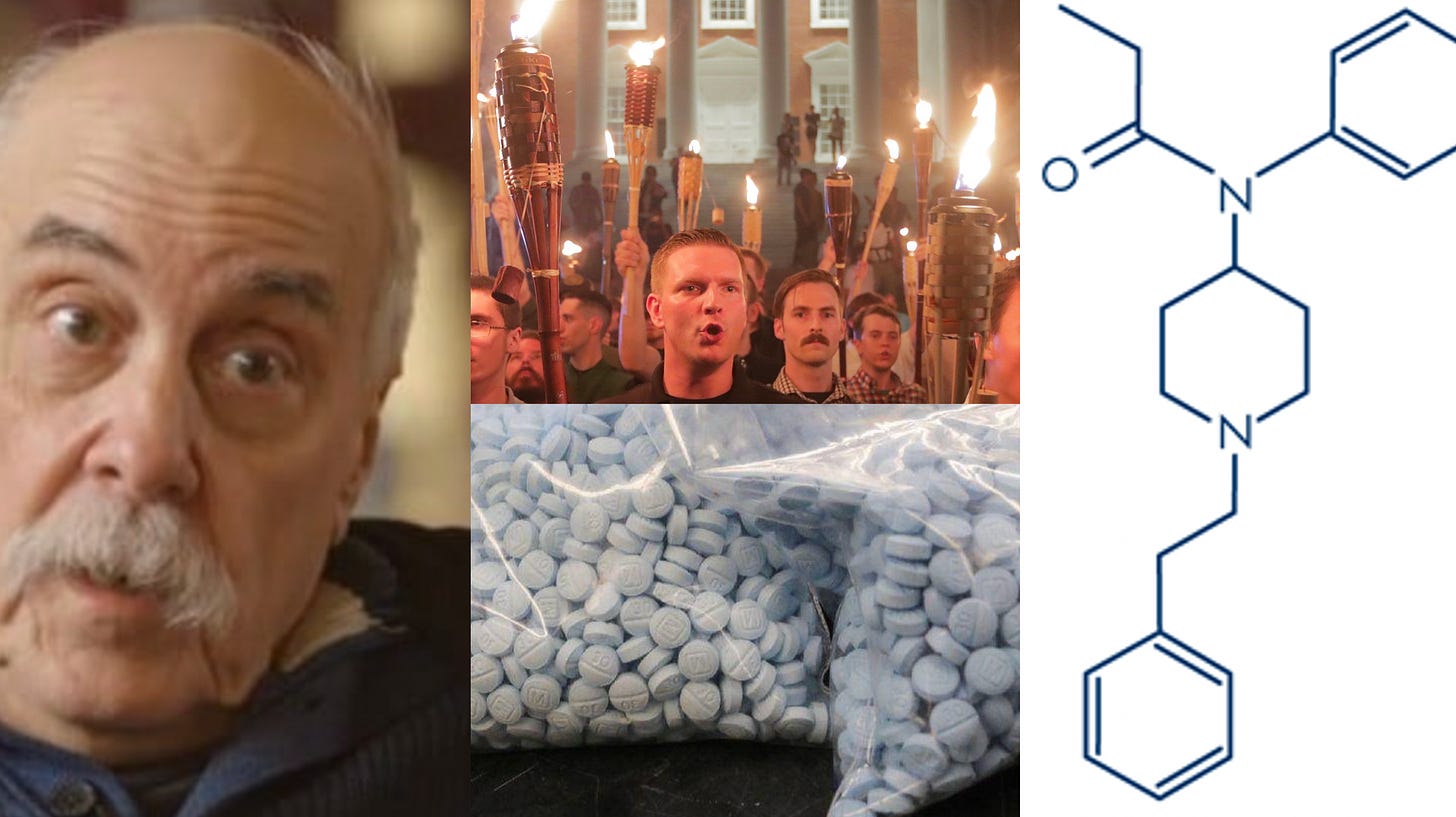

Yesterday, news broke of the death of a neo-Nazi named Teddy Joseph Von Nukem. Von Nukem had been known as one of the figures involved in the deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017. The disturbing violence at the rally resulted in one death and numerous injuries and left a deep impression upon the nation at large, symbolically marking the start of the Trump era.

Four years later, Von Nukem was stopped at the US-Mexico border by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents. The CBP agents found “15 kilograms of fentanyl pills hidden behind the seats and floor compartment of his 2019 Nissan Pathfinder,” according to The Daily Beast. “Von Nukem quickly admitted that he had been paid 4,000 Mexican pesos (around $215) to smuggle the pills into the country” as Jose Pagliery reported.

Law enforcement pressed charges. But Von Nukem never showed up for trial. Instead, his nearly-dead body was found lying in the snow behind a shed in his backyard with a gunshot wound. His wife had located him and immediately called for an ambulance. As Pagliery reports, Von Nukem still had “a faint pulse” when the paramedics and police got there. But he died shortly thereafter. His death was ruled a suicide.1

There are clearly a lot of dimensions to this case, but the one I will focus on here is the fentanyl connection. Why, one may wonder, would a neo-Nazi want to smuggle drugs? Is this a unique case or a regular occurrence? When did neo-Nazis become interested in fentanyl?

As it turns out, these questions are all answerable. I know because I have spent the last few years researching the political aspects of today’s global illegal drug trade. And, as I’ll demonstrate, this particular case of neo-Nazi drug smuggling is in no way unique. In fact, there is a long (and a bit disturbing) history of Nazi involvement in the global drug trade.

Roots in World War 2

In order to understand this web of issues, it is best we start at the beginning. Before neo-Nazis and fentanyl, there was the original Nazi party of Germany. Many top Nazi officials used opioids, cocaine, and amphetamines regularly throughout their careers. Methamphetamine was actually part of routine military protocol for Nazi troops as they tried to take over Europe in World War 2.2

But the Nazi’s interest in drugs went beyond personal consumption. They also employed mescaline, barbiturates, and a number of other drugs in a series of abusive experiments on prisoners in the concentration camps at Auschwitz and Dachau. As the war ended, US troops liberated the concentration camps. They also seized documents which described the drug research that had been going on there. As Norman Ohler wrote in Blitzed,

“It was a treasure trove for the US Secret Service. Under the leadership of Charles Savage and Harvard medic Henry K. Beecher, the experiments were continued under the code name Project Chatter and other rubrics at the Naval Medical Research Institute in Washington, DC.”

The Nazi’s research inspired a tidal wave of similar work in the US in the postwar years, as a series of projects were launched to achieve comparable—or even better—results.3 The most infamous among these was MK-ULTRA, but it was just one of many such projects.

Nazi involvement in post-war heroin boom

And the US government didn’t just use the Nazis' research. They used the Nazi scientists themselves. As has since been revealed in declassified documents and firsthand interviews, certain elements in the US government (specifically, the CIA and numerous top military personnel) ran an extended project known as Operation Paperclip in which roughly 1,000 top Nazi scientists and military personnel were exempted from legal persecution and spirited out of Germany to various positions throughout the Western hemisphere. 4

Around the same time, the CIA also began to employ former Nazi military personnel to help fly loads of opium and heroin out of the Golden Triangle.5 The Golden Triangle opium trade was dominated by Chinese triads who had expanded into Southeast Asia as the Communist Party of China took control of their home country. Because they opposed the Communists, these networks of Chinese émigrés were embraced by the US military and intelligence apparatus as strategic partners in the Cold War. The Italian and French mafias also collaborated with the US government for similar political reasons.

The Nazi pilots therefore found themselves amidst a web of actors who made up what has since become a global network of drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) spanning from the Golden Triangle to Marseilles to Sinaloa to Vancouver, and beyond.

The birth of fentanyl

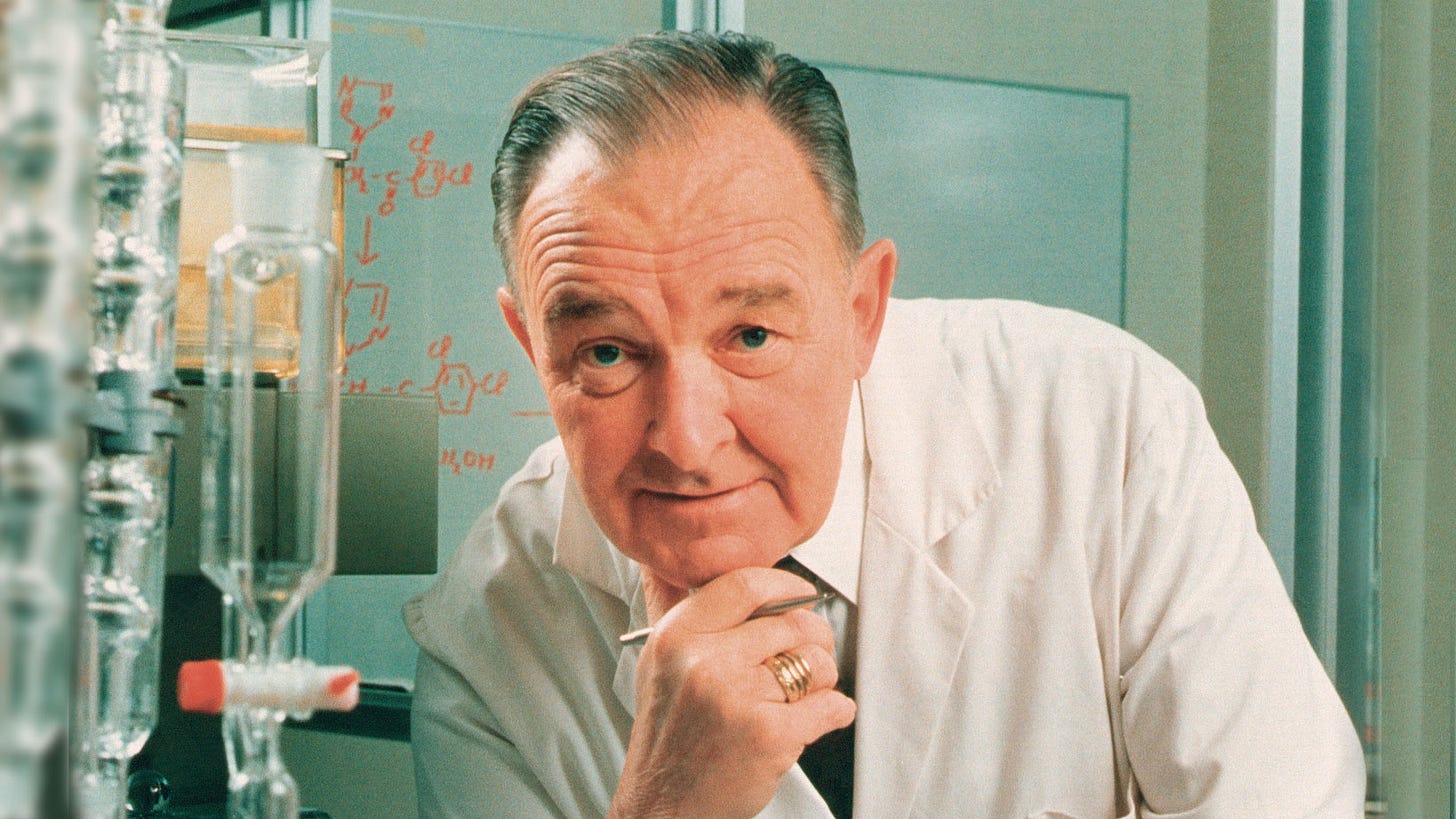

As the Cold War heated up, a chemist named Paul Janssen (the namesake of Janssen Pharmaceuticals, a subsidiary of Johnson + Johnson that sells esketamine) invented fentanyl in 1959. Widely known by now, fentanyl is a synthetic opioid designed for surgical use. But it would be several decades before the drug gained widespread popularity.

Janssen had warned that his creation could easily inspire habitual use and knew that, due to its potency, it was much more prone to overdose and other adverse outcomes compared to other opioids. For years, fentanyl remained an obscure drug and his warning was mostly ignored. But in time, the drug and its analogues would take over the global opioid trade.

While the CIA was working with Nazis and the various European and Asian DTOs, they also cultivated connections with DTOs that were expanding on US soil. One of these was the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, or BEL, a California-based crew that began in the late 1960s and obtained their LSD from intelligence-connected sources. The BEL quickly assumed dominance in the global cannabis, hash, and acid trades and carried out their business with military-like precision. In fact, many of the individuals who made up the BEL had themselves served in the military, a number of them as Marines. It is just one of countless examples in which military personnel have served as catalysts for drug distribution.

Enter William Leonard Pickard

The BEL were peaking at the height of their power in the early 1970s when the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) was born. The agency, itself a successor to the the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) and the Federal Bureau of Narcotics (FBN) before it, was officially launched in 1973.6

Not long thereafter, a young chemist named William Leonard Pickard walked into the DEA’s new San Francisco office. There, he reportedly offered to act as an informant against the BEL.7 Not surprisingly, the DEA did not need Pickard’s help going after the BEL (which was, after all, a CIA-affiliated organization). But they did use him to help bust methamphetamine laboratories as well as “a rival LSD operation” according to journalist Dennis McDougal.8 It was just the beginning of Pickard’s decades-long relationship with the DEA.

Just two years later, in 1975, Pickard’s personal mentor, Alexander Shulgin—another drug chemist who worked extensively with the DEA—wrote a paper in which he warned of the potential street use of fentanyl. In the piece, titled “Drugs of Abuse in the Future,” Shulgin explored some of the many potential candidates for synthetic drugs which he predicted might gain popularity in the following years. He mentioned fentanyl specifically as just such a drug, and wrote that the emergence of synthetic heroin substitutes like fentanyl was a matter of “when,” not “if.” He was right—before the end of the decade, the first reports of fentanyl among street users appeared.9

[In Part 2, I discuss George Marquardt, a neo-Nazi chemist who was among the first to distribute large amounts of fentanyl on the street. I also discuss more recent cases of neo-Nazis distributing an assortment of drugs including fentanyl, heroin, methamphetamine, and ketamine, plus a case in which neo-Nazis were found to have made plans to manufacture and distribute DMT.]

As Jose Pagliery noted, the resulting coroner’s report said that “suicide notes were found at the scene…however handwriting was somewhat inconsistent.”

See Norman Ohler, Blitzed: Drugs in the Third Reich, throughout.

“It was a treasure…” quote and information about US embrace of Nazi research from Ohler, p. 210-211.

Operation Paperclip was carried out against the wishes of multiple presidents and a plethora of top government officials who greatly resisted such attempts to protect or collaborate with Nazis. The Nazi-allied wing of the government, however, which included figures such as the Dulles brothers, John McCloy, and Henry Stimson, realized that their efforts faced political opposition and so proceeded to conduct the operation covertly and without the knowledge of President Truman. See Annie Jacobsen, Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America, throughout.

See Martin A. Lee and Bruce Shlain, Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond, p. 12.

Within a few months of its formation, the DEA put together a Special Operations Group (DEASOG). The DEASOG was staffed with twelve former CIA agents. Among them were veterans of the agency’s Phoenix program in Vietnam, as well as their capture of Che Guevera and their ousting of Chilean president Salvador Allende. The team at DEASOG was assembled by Lou Conien, who had worked at the CIA under William Colby. Not coincidentally, Colby became the director of the CIA around the same time that the DEA (and shortly thereafter, the DEASOG) was created. Thus, the bureaucratic connection between the DEA and the CIA were strong, if hidden, from the beginning. See Douglas Valentine, The Strength of the Pack: The Personalities, Politics, and Espionage Intrigues that Shaped the DEA, p. 193-194.

See Dennis McDougal, Operation White Rabbit: LSD, the DEA, and the Fate of the Acid King, p. 89.

Ibid.